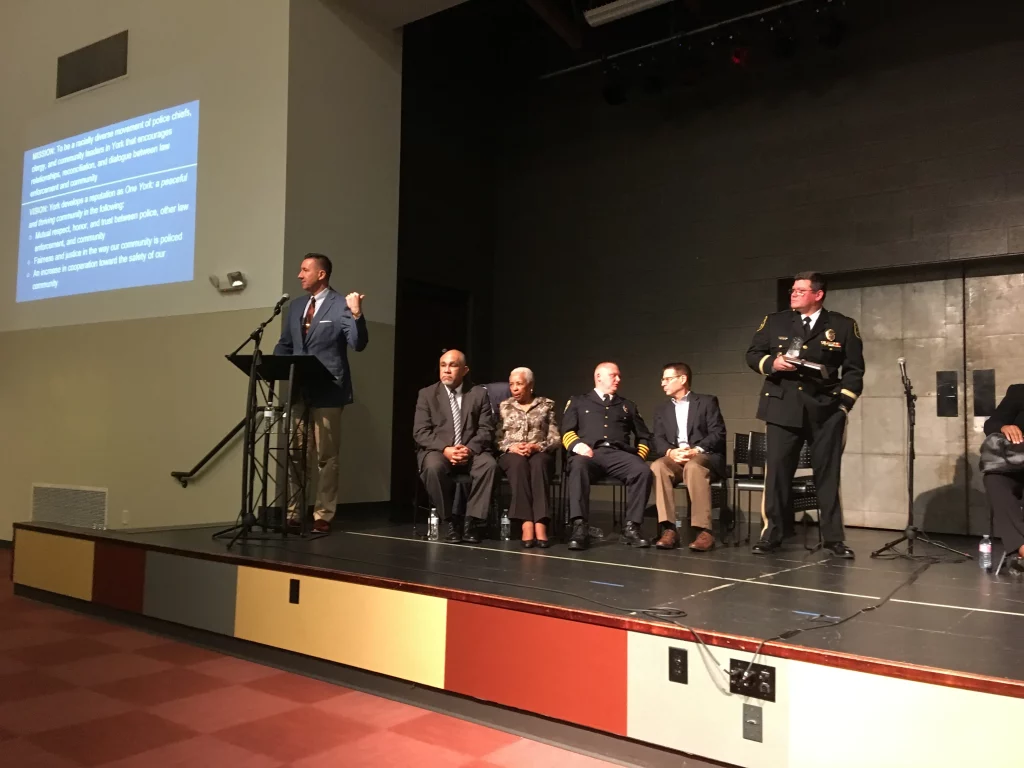

York County police-clergy alliance Formed common ground

Chiefs & clergy partnership

250 W. King St., York

The situation

More than 50 York County clergy sat on one side of the Logos Academy auditorium. On the opposite side of the room, sat law enforcement. An invisible veil divided them on that 2016 evening. “There was so much tension in the room,” says Pastor Bill Kerney from York’s Covenant Family Ministries. “No one knew what to expect.”

“This was the first time that clergy and law officials sat down at the table and had a dialogue,” he says.

A few months prior, a Baltimore man named Freddie Gray was killed while in police custody. Baltimore flared with pent up bitterness toward the racial discrimination that had wounded the community for decades. Some in York County feared that unrest would radiate across the Mason-Dixon line.

Kerney, aware of York’s own tense past with the nearing 1968-69 York Race Riot anniversary, wanted to get ahead of any local disputes. He called Aaron Anderson, CEO of Logos Academy, who reached out to contacts in law enforcement contacts that gained from years of building relationships in the community.

“As leaders in our community,” Aaron Anderson wrote, “we were keenly aware that our city was on the brink of potential riots if even one police interaction went wrong.”

Together with the Black Ministers Association, Anderson and York City’s former Police Chief Wes Kahley invited the other chiefs across the county. But while they saw the importance of such a meeting, the chiefs expressed concern that an ambush awaited them.

The witness

What happened in that Logos Academy auditorium?

Pastor Ramona Kinard approached the mic at the front of the room with a grievance. Her young, Black son had been followed, almost every night, on his ride home into York City. Others on her side of the room nodded their heads up and down in remorseful understanding. She was tired of her son coming home scared. She was tired of the police targeting her son.

Next to the mic was Dan Stump, chief of Springettsbury Township Police Department at that time. The room was silent as they anticipated his response. He could have launched into an explanation, defending his officers’ choices.

Instead, he apologized.

“You could see the passion and the hurt,” Kerney recalls. “He couldn’t believe what he was hearing.” But he owned it and believed an apology was due.

One remark clearly broke the tension in the room. Kerney remembers Chief Mark Bentzel, the current Northern Regional Police Chief, saying something like this: “Listen, as police officers we don’t get it right all the time.”

“Wow,” Kerney reflects, shaking his head side to side at the memory. “They’re human. We have to remember this. Police officers are human, too, and they’re going to make mistakes. “

One by one, for three hours, clergy and police approached a mic with Anderson moderating.

For years, in fact, the two groups kept their meetings maybe low key. Not because they had anything to hide. But because they wanted to create a safe space to openly share, ultimately building relationships.

The objective of that first meeting was to head off unrest before it reached York. And while many other factors played a role in many in the York community’s ability to peacefully protest, it worked. And it continued working years later when another Black man lost his life at the hands of the police.

When George Floyd of Minneapolis was killed in 2020, Yorkers gathered for a Black Lives Matter protest. Locals heard of the rioting elsewhere across the country, but York County was different. Mostly led by youth, the organizers held homemade signs and spoke words calling for justice.

“It would have just took one little spark,” says Pastor Kerney. With the many shootings and movements to defund the police, “The nation was in turmoil.”

This moment in York history gave the chiefs and clergy a great opportunity to stand in unity. The moment cemented their union, and they wrote a joint statement denouncing the brutality.

The two groups had learned that they could trust each other. “Listen, we’re not here to point fingers,” Kerney says. “We have to be able to forgive.”

“A part of it from the police side was developing that empathetic ear,” Chief Todd King from Springettsbury remembers. “We don’t know what we don’t know.”

King acknowledged what might seem fair to the police officer might not translate to community members. So, police across the county developed trainings such as unbiased police training and procedural justice.

Of course, they invited the clergy who witnessed how officers trained, and they got feedback on how it impacts the community. “It lets us learn from each other,” King says.

This partnership wouldn’t have worked without the humility of two groups: The Black Ministers Association and police from across the county.

“I am not going to open my heart to you if you are going to trample it,” Anderson wrote. “The act of trust is one of vulnerability. We knew that relationship-building was going to take years, not days, weeks, or months.”

But over time, the meetings unlocked another path toward trust between the community and police. The York County Safety Collab was born in 2022 to facilitate collaboration between the 17 police departments, DA’s office, and the community.

Here are some of the changes that came from the Chiefs and Clergy Partnership:

- Local Black pastors and leaders attend training sessions to speak to officers on topics such as implicit bias.

- Police attend more community events, including church gatherings where members pray with and for law enforcement.

- They organize more block parties where police are welcome.

- The two groups promote each others’ good work on social media and through their networks.

The questions

Chief Todd King says one of the biggest benefits of the meetings is that he now has a set of advisers. He can go to them, asking how to address certain complicated topics. “Then I’m not just addressing it from my point of view,” he says. “I’m addressing it from a collective point of view.” In what ways are you creating your own board of advisers for your vocation or for your life. Who can you go to for a different point of view as a way to check your logic? Could you form your own “board of advisers” who help you navigate tough decisions?

Isn’t this a prime example of how a community – Logos, the Black pastors and police – can work through issues without waiting for government to convene, intervene or solve?

Related links and sources: Check out this additional page on Witnessing York that outlines our communities’ long, racial struggle; Anderson’s 9 Proven Strategies for Breaking Through to Common Ground; Chiefs & Clergy Partnership. Top two photos, Chiefs and Clergy. Middle two photos, York Daily Record. Bottom video by York County Safety Collab.

Note: Jamie Noerpel, co-author of this piece, is an employee of LogosWorks and facilitates the York County Safety Collab.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE