Earl Shaffer’s thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail

A soldier’s escape:

Healing PTSD in nature

Appalachian Trail half-way point

1120 Pine Grove Rd, Gardners, PA 17324

The situation

Civil War physicians examined anxious, battle-weary soldiers and found the answer to their rapid pulse rate and raspy breathing: It was not in their heads. They called it “soldiers heart.”

The formal recognition of combat trauma by medical professionals came in the tents at these military hospitals. The treatment? They gave these fighting men symptom-controlling drugs, and they were sent back to the battlefield.

Scott Mingus and James McClure include a story in Civil War Stories from York County, Pa.: Remembering the Rebellion and the Gettysburg Campaign about Daniel E. Blouse from Chanceford Township. He faced spinal damage and later shell and gunshot wounds while serving, and the death of his wife after discharge. Eventually, his hallucinations made him a danger to his wife and daughter, so he was institutionalized at the State Insane Asylum in Harrisburg, dying there in 1896.

Philip Cole describes more in YOU’LL BE SCARED. Sure-you’ll be scared: Fear, Stress, and Coping in the Civil War. As is the case during any conflict, the grave consequences of war require physical and mental preparation. The reaction to flee danger must be managed.

During the First World War, “soldier’s heart” changed to “shell shock” or “war neuroses.” Doctors originally speculated that large guns caused brain damage, until soldiers far from explosions displayed matching symptoms. Treatment included a few days of rest, daily exercise, and even hydrotherapy and electrotherapy in Europe — today considered inhumane therapies. Some used “horticultural therapy” as a way for soldiers to build relationships with nature, something that wouldn’t gain traction for years.

“Combat Stress Reaction” and “battle fatigue” replaced previous terms during World War II.

For the first time, treatment was taken seriously with immediate rest and complete recovery before rejoining the fight. Preventative measures were even in place, such as stress prevention through bonding within the military units. Even though half of those medically discharged from the military suffered “combat exhaustion,” major military leaders – Gen. George Patton was one – refused to accept the reality of trauma caused by war.

Just as World War II doctors saw relationships as a way to prevent trauma, many veterans expanded their relationships to nature as a way to reestablish their mental health.

The witness

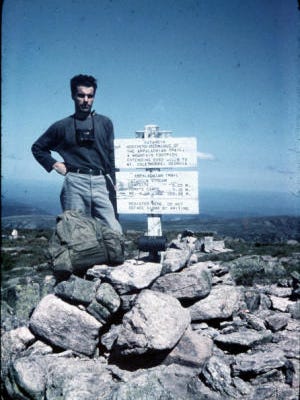

Earl Shaffer from York County, served in WWII. Once released, Shaffer became the first person to thru-hike the Appalachian Trail, traversing 2,020 miles in 124 days. We do not know if Shaffer suffered from PTSD, but his 1948 trip started as a search for mental clarity from the psychological impacts of service.

His childhood friend, Walter Winemiller, had died in Iwo Jima. They grew up in Shiloh together, spending as much time as they could outside trapping, fishing, hunting, finding arrowheads, and hiking.

“The loss of his childhood friend and hiking partner had a profound impact on Shaffer,” writes Silas Chamberlain, author of On the Trail: A History of American Hiking and a York County resident. Chamberlain quotes Shaffer’s diary: “Miss your voice, the touch of your hand. My buddy, my buddy. Your buddy misses you.”

Shaffer’s depression impacted his ability to find employment and eventually his odd carpentry, restoration, and antique dealing jobs. “Those four and a half years of army service, more than half of it in combat areas of the Pacific, without furlough or even rest leave, had left me confused and depressed,” Shaffer wrote. “Perhaps this trip would be the answer.”

Shaffer described his foundational hike in Walking with Spring: The First Thru-Hike of the Appalachian Trail. To be a soldier, he had to survive in nature. His life depended on his relationship to the land. Shaffer didn’t know it at the time, but scientific research shows that time outdoors can help the healing process.

According to an article in Health Psychology Open, treatments of PTSD include a variety of natural settings such as forests and therapy gardens with positive outcomes. A group of researchers studied soldiers suffering from PTSD at Nacadia, a therapy forest garden. Walls of plants, ceilings of leaves, and walls of vines create a feeling of immersion.

There, soldiers participate in mindfulness activities, sensory experiences, breathing techniques, and yoga. They discussed and contemplated problem solving and conflict resolution while in “sheltered places” in the gardens. They split wood, plant trees, and build bird boxes. By doing so, the veterans reported satisfaction from feeling useful as well as giving back to nature.

Shaffer also created a shelter in the woods on his hike. While in Pennsylvania, he slept under the mountain sky without a tent. “My bed was a mat of spruce needles back of a rock,” he wrote. “The Trail was only a few feet away but the average person would never have spotted me.”

Likewise, the veterans in Nacadia preferred remote areas far from others. One leaned his back against an earth bank. Another sat on top of a wooden platform so he could see the area all around him. Yet another preferred a large tree with branches that cascaded all around him to the ground, creating a hidden shelter.

Shaffer frequently described his observations, smells, sounds, and feelings while hiking. These sensory experiences helped him experience the moment — a form of meditation. Comparably, the veterans at Nacadia used the scents of the flowers, dampness of the soil, and changes of sunlight to increase their attention to nature.

For some, the rain held specific importance. Listening to the rain soothed their anxiety, as well as the way it kept fair-weather visitors away. The rain purified them.

Shaffer usually did not like the rain. The water soaked his clothes and turned his boots soggy. When sleeping in one particularly swampy area, he wrote “It was one of those long, long nights….More murky weather and overgrown trail greeted me in the morning.” Yet, Shaffer found ways to lift his spirits. “As a last resort I started singing to cheer myself up,” he wrote. “If anyone had heard he surely would have thought a lunatic had escaped somewhere.”

When Shaffer reached the end of his journey, he “wished that the Trail really was endless, that no one could ever hike its length.” Nature made no demands on him. It accepted Shaffer, and other veterans suffering from PTSD, just the way he was. The trees, the plants, the rocks, and the mountains release the disturbing thoughts that haunt their minds.

It’s difficult to find the DSM-5 online, but the National Center for Biotechnology Information published the criteria for PTSD on its website. Here are a few of the symptoms:

- Reoccurring, involuntary, and intrusive memories of the traumatic event that cause distress. This could be in the form of dreams or flashbacks.

- Avoiding the stimuli connected with the traumatic event such as people, places, objects, activities, conversations, situations, memories, thoughts, or feelings.

- Negative moods attached to the traumatic event by failing to remember, exaggerated beliefs or expectations, distorted memories, loss of interest in activities, detachment from others, and the inability to express positive emotions.

- Changes in behavior such as angry outbursts, recklessness, and difficulty concentrating.

The questions

How can we better serve the veterans who fought for our freedoms? In what ways can York County create places for people suffering from PTSD to feel safe?

Related links and sources Tin foil dinners and blow-up mattresses: Not Earl Shaffer camping but just as fun by Jamie Kinsley; The Earl Shaffer Foundation, Appalachian Trail’s Earl Shaffer made mark and First Appalachian Trail through hiker: ‘Mention the name Earl Shaffer, it’s awe, integrity, respect’ by Jim McClure. Photos, York Daily Record.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: Hometown History - Explore people, places and issues - Witnessing York

Pingback: Hometown History - We walk the line: On the rail trail from New Freedom to York, Pa. S2, E5 - Pennsylvania Digital News