Peering Through Elmwood’s pillars: Witness to a changing York County

Elmwood Mansion

400 Elmwood Blvd, York

The situation

The family that lived there for 70 years – the J. Edgar Small family and its forbears – called it Elmwood House.

But it has taken on the name of “mansion,” and landmark, built as a farmhouse, has stood at York’s eastern gateway since about 1835.

Today, it’s a quiet place with a refreshed bit of bustle – it’s the new headquarters for Inch & Co. real estate and property management.

But for years – on its grounds and in its shadow – it has witnessed change, sometimes biting and difficult and sometimes the quiet evolution of an agricultural county growing up.

The witness

This is but a small sample of big moments that Elmwood Mansion residents would have witnessed from the farmhouse’s front and back doors:

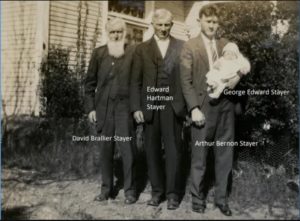

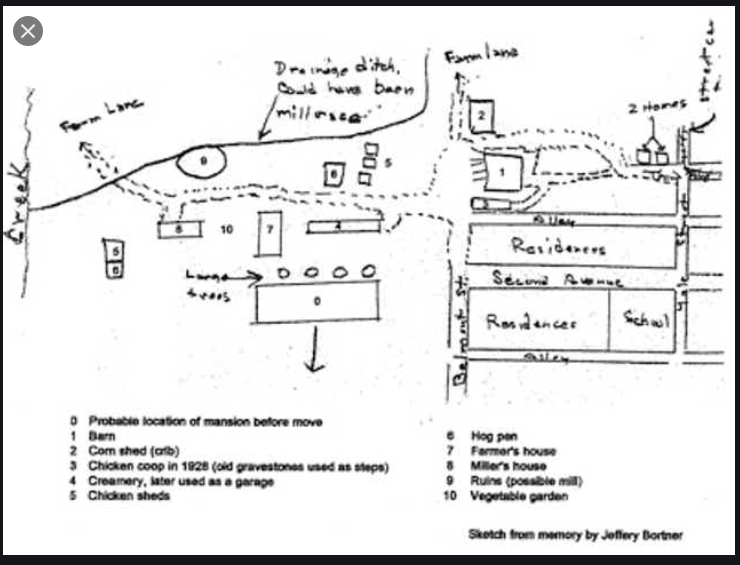

When the Elmwood House went up about 1835, the site was a working farm, then several generations old. The farm’s acreage would host barns, a mill and other outbuildings, perhaps typical of many York County farms of its day. Farm owner Jacob Brillinger’s house stood at the time near the present-day intersection of Belmont Street and Second Avenue in Spring Garden Township.

This was a period in which enslaved people seeking freedom from the South moved through York County, and for decades Elmwood became associated with the Underground Railroad. In his recent book “Guiding Lights,” historian Scott Mingus considered Elmwood a “reported” Underground Railroad station.

“Brillinger reportedly hid freedom seekers in two attics until they could be safely taken east to Wrightsville, though documentation is scarce. Trap doors allowed entry and exit to a back hallway over the kitchen or to a third-story bedroom,” Mingus wrote.

Elmwood’s location near the main road from York to Wrightsville might have made it a candidate for a Underground Railroad station, but it’s certain the proximity to this good road made it desirable to Confederate soldiers invading York County in late-June 1863. Hundreds of enemy soldiers passed it as they moved back and forth to Wrightsville, foraging along the way.

Indeed, a Confederate cavalry unit used the Brillinger farm as a camp, and its troopers and horses exacted a heavy toll: 247 bushels of corn, 68 bushels of oats, 22 acres of hay and most of the farm’s fences. They ordered the Brillinger family to serve 300 meals with 6 barrels of whiskey.

Among other things, this painful enemy requisition gives a glimpse of the prosperity of the Brillinger farm.

Fifty years later, Elmwood survived two fires that took other buildings on the farm. Fires, then as now, plagued barns and other structures in farming operations. The family of J. Edgar Small, owners of Elmwood from 1887 to 1957, says tradition cites the fires and threat of more blazes as a reason that mules and greased logs were deployed to move the farmhouse 660 feet north in 1905. But more research by the family indicates the need to add to dwindling farm income with proceeds from real estate sales might have prompted the move of the house to its current site. The Small family had the real-life challenge faced by many owners of farmland – the decision of selling off lots to save the farm. The best bet that the threat of fire and the need to make room for development combined to bring in the mules, logs and grease.

This long-time tug of war between agrarianism and development in York County continued to play out at the farmhouse and its farm. Despite the move to 400 Belmont Boulevard, the land remained a working farm with barns and related buildings. That is, until 1951, when the rest of the undeveloped part of the old farm was sold, the buildings razed and the subdivision expanded.

In 1959, Interstate 83 officially opened, and a superhighway now ran within a literal stone’s throw from the old farmhouse, with an on-ramp gobbling part of its front yard. But the house remained standing, sans the venerable Small family, who had sold Elmwood in 1957.

The house would change hands at times after that, leaving doubt about whether this architecturally and historically important farmhouse, set on desirable commercial land, would survive. Now, after remodeling by Inch & Co., the Elmwood Mansion has gained another life. It’s an intriguing irony that a farmhouse threatened for years by development would be rescued by a construction company – one that saw to it that the landmark would be preserved.

Small family member and architect Robert Niess, in a recent interview with the York Daily Record, put his family’s longtime home into perspective:

“But despite the property development and later the construction of the freeway, the grand old house remains one of the few houses of that era that is still capable of expressing its older relationship to the landscape and its agricultural basis. In a certain sense, the subdivision also tells a tale of hardships and struggle and the transition from a working farm in a changed economy. Through its ability to ‘speak,’ I strongly feel that the house really belongs placed under historic preservation.”

He ended his interview with these thoughts: “

“I sincerely wish that the old house, with its new owners, can be treated and maintained inside and out as the historic monument it is. The building and its site has a lot to tell and is clearly part of the identity of what makes York, York. The idea of a historic monument is, however, not only about preserving the authenticity of the past but allowing it to continue to address the present.”

The questions

One of the missions of Witnessing York is to recognize places of historical importance. We believe the Elmwood Mansion fits the criteria as one of those noteworthy places because of its role in assisting freedom seekers, food production, and industry. As Robert Niess says, the building “has a lot to tell.” How can we ensure these stories continue to be told, and not lost to the annals of history? As keepers of history, how do we pass this knowledge down to future generations?

Related links and sources: Scott Mingus’ ‘Guiding Lights’ and ‘Flames Beyond Gettysburg,’ James McClure’s blog post: Elmwood Mansion ‘conveys an almost iconic sense of home.‘ Photos from York Daily Record/Sunday News’ files.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE