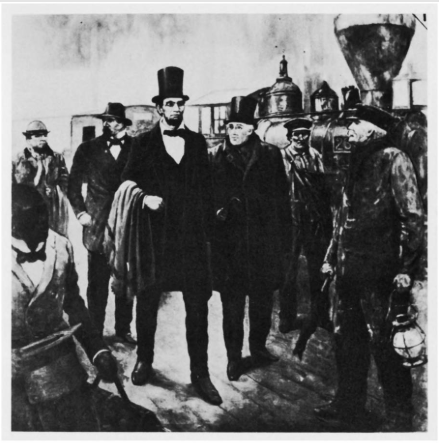

William Henry Johnson, President Lincoln’s aide

Hanover Branch Railroad

Near Park Avenue and Railroad Street

Hanover

The moment

Matthew Jackson writes this guest column from Hanover about two moments in that southwestern York County town when Abraham Lincoln arrived and departed. The president was in the region on his trip to Gettysburg where he would deliver what is today known as The Gettysburg Address.

On this round trip and in the White House, his personal valet, William Henry Johnson attended to him. Lincoln’s only speech in York County came in Hanover, during a brief stop on the way to Gettysburg aboard the Hanover Branch Railroad. On Lincoln’s return trip on the Hanover Branch, Johnson attended to the ailing president.

Matt Jackson, an inspiration for Witnessing York and an advisory board member, tells this story with an assist from journalist/historian Marc Charisse:

Multitask-master William Henry Johnson

On November 18, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln was not feeling well.

Our 16th president looked “sallow, sunken-eyed, thin, [and] careworn.”

The long, jostling train journey from Washington, D.C. to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania didn’t help. Our Civil War commander-in-chief likely was falling ill from a deadly virus, a form of smallpox.

With Lincoln on his trip to and from Gettysburg was the hard-working William Henry Johnson, the president’s trusted African-American valet and multi-tasker.

They had history.

A freedman, Johnson worked for the Lincolns in Springfield, Illinois. In 1861, Johnson assumed the role of bodyguard when he accompanied Lincoln on a fraught rail journey from Illinois to Washington, D.C. On route, they stealthily changed trains in Baltimore, where rumors of an assassination attempt on the president-elect reached a fever pitch. Lincoln was even dressed in disguise.

Throughout his tenure working for Lincoln, depending on the situation at hand, the trusted Johnson served as the president’s groomer, bodyguard, fire-keeper, driver, bootblack, barber, butler, valet, and errand runner.

On the morning of November 18, 1863, Lincoln made sure his indispensable man was with him.

Lincoln sent a note to the Department of Treasury, where Johnson worked in addition to the White House, that simply said, “William goes with me.”

As they departed D.C., mortality and uncertainty must have been on their minds. Not only were they traveling to the site of the bloodiest battle of the war, which devastated and traumatized the small town of Gettysburg, but Lincoln’s son Tad was diagnosed with smallpox that day. The virus’ epidemic was starting to spread throughout the capital, and the outcome of the war still hung in the balance.

Johnson was the only known person of color on the presidential train to Gettysburg.

From D.C., their Northern Central Railway train rumbled to Baltimore, then north over the Mason-Dixon Line to New Freedom and Glen Rock before stopping at Hanover Junction in Seven Valleys. There, Lincoln and his entourage, which included Secretary of State William H. Seward, “a bevy of reporters and politicians”, and staffers private secretary John G. Nicolay and adviser John Hay, boarded a Hanover Branch rail train.

That engine chugged nine miles to Hanover, where Lincoln gave a brief speech, then another 14 miles west to the downtown Gettysburg train station. From there, he walked a couple blocks to attorney David Wills’ house, where he stayed for the night.

But Lincoln still had work to do that evening on his “few appropriate remarks” in his upstairs room.

Johnson was right by his side, serving as messenger when the president needed services from their host.

Based on Johnson family oral history and Wills’ recollections, some historians surmise that Johnson, upstairs in the Wills house, was the first person to see and hear the final Gettysburg Address. See Gabor Boritt’s The Gettysburg Gospel (2006).

“Johnson was close by during the time Lincoln was upstairs (in the Wills House), undoubtedly taking care of the many details involved in an overnight presidential visit,” notes historian Martin Johnson. “He almost certainly was one of the very few who witnessed Lincoln working on the speech that would proclaim a ‘new birth of freedom.'”

According to documentarian Ken Burns’ famous The Civil War, Lincoln, in his ten sentence, two-minute, 269-word speech, “went on to embolden the Union cause with some of the most stirring words ever spoken.”

But Lincoln had no way of knowing the speech’s deep impact in the immediate aftermath. In fact, said Civil War historian Shelby Foote: “[Lincoln] felt that he had failed, that it was a poor speech, that the people didn’t like it. … Lamon, his friend Ward Lamon, who was sitting next to him on the stand when he sat down. There was just a sprinkling of applause. And he said, ‘Lamon, that speech won’t scour.’ That’s what you say about a plough in the prairies when the mud doesn’t come off it.”

Over time, Lincoln’s speech proclaiming “a new birth of freedom” “of, by and for the people”, became world famous. Part Greek eulogy and part transcendental vision quest, his poetic prose became heralded as a clear, strong articulation of American national unity, devotion to principles, universal freedom and democracy. Some call it our nation’s second Declaration of Independence. Long-time journalist Tom Brokaw calls it “America’s gospel.” It also is known as the most quoted speech in American history.

But the crest-fallen Lincoln had no way of knowing the impact in the immediate aftermath. After the cemetery dedication, the president and his entourage, including Johnson, returned to Washington, D.C. the same way they came — through Hanover, Hanover Junction and southern York County to Baltimore and finally to D.C.

On their return trip, the now melancholy Lincoln showed symptoms of variloid, a form of smallpox. Lincoln lay “in a relaxed position with a wet towel across his head.”

Johnson served as Lincoln’s nurse the entire way to D.C., with their train not arriving until midnight.

Unlike the trip to Gettysburg, Lincoln’s return train did not stop in Hanover or Hanover Junction for several reasons. Lincoln was tired, showing effects of the infection. He was depressed. It also was getting dark.

As historian Scott Mingus, Sr. states, “It also was late in the day, and he had been mingling with crowds all day before and after giving the short speech, including going to a church service. He needed rest.”

After Lincoln returned to the nation’s capital, he eventually recovered. Soon after, however, Johnson fell ill. By January 12, 1864, Johnson was admitted to a hospital. He died that same month of smallpox. A good possibility exists that William contracted the disease from the 16th president.

Whether Lincoln felt guilty for Johnson’s death at the hands of the virus is unknown, but Lincoln’s actions after Johnson’s death show loyalty to, if not affection for his dutiful aide.

Lincoln paid for the mortgage on the D.C. house where Johnson’s growing family lived.

The president also paid off half of a loan of Johnson’s that Lincoln had cosigned. The banker canceled the debt’s other half.

Further, Lincoln paid for Johnson’s burial expenses. According to credible historians, but not without a difference of opinion, William Henry Johnson is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, one of the first African-Americans buried there.

Etched on the tombstone purported to be Johnson’s is the simple title “Citizen”, a status that eluded him during his short lifetime (1835-1864). Granting full U.S. citizenship to African-Americans, the 14th Amendment was not passed until 1868.

Lincoln was elected to a second presidential term in November, 1864 and took office in January, 1865. In a planned assassination, famous actor John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln on April 14, Good Friday. The next morning, Lincoln died at the age of 56, just days after the Confederate surrender in Appomattox, Virginia.

Honoring William H. Johnson through public art

Illuminating hidden, neglected and little-known places and peoples of our communities’ pasts can help us appreciate the kaleidoscope of humanity and humaneness that have enriched our culture and lives.

No prominent public art or public signs recognize William Henry Johnson in York or Adams Counties. It is altogether fitting and proper that we do so. Perhaps one outdoor storyboard each at the Hanover library and Hanover Junction in Seven Valleys are in order? The old, beautifully restored downtown Gettysburg train station would be another fitting location. Other public art? An official Pennsylvania Historical Museum Commission marker at the library? What do you think?

The questions

How people treat “the help” is telling of their character. We don’t know exactly how Lincoln treated Johnson, but his payment for Johnson’s burial expenses leads us to think that he showed people respect. Modeling Lincoln, how can we better treat the people who serve us? The wait staff at a restaurant? The Uber driver? The custodians at our work?

Related links and sources

Top photo by York Daily Record. Middle photo, Bill Swartz. Bottom photo, Washington Evening Star.

Pingback: Arthur Evans - Prominent activist grew up in York - Witnessing York