makeover designed to repair damage inflicted on York County waterway

Some see foul canal, but Codorus Greenway to turn creek into park

Richland Avenue, York PA

The situation

Codorus Creek has graduated from its “Inky Stinky” class, but few would call it a winsome waterway, with those high banks and scant creekside access. Years of use – and abuse – have damaged the York Countian’s image of what could be.

But modern perceptions can’t alter the fact that the Codorus shaped York County culture from its indigenous peoples through colonialism and into the 21st century.

Hundreds of thousands of people have relied on it for hydration, agriculture, recreation, energy, transportation of our goods, and even supporting our nation during times of war. But it’s also been used to dispose of our waste. It’s been so polluted that fish could barely live in it.

The Codorus Greenway project is seeking to rehab the part of the creek that runs through York, making it a city recreational showpiece. Plans call for more creek access to fish or boat, places to sit along its bank and a new trail on the west bank to offer the same recreational fun provided by the York County Heritage Rail Trail on its east bank. That park and trail also will connect west end neighborhoods with the downtown and with each other, giving a way for many to walk or bike to work.

This project will broaden the way people view and use a one-mile stretch of the creek, transitioning the waterway from flood control alone to an enjoyable park and trail system that will still keep the city and its people safe in heavy rains.

The witness

Crispus Attucks York has taken the lead in educating students about the creek and neighborhoods. Jeff Kirkland, local historian, taught a group of students about the Black families who lived in the nearby South Penn Street, many who migrated from Bamberg, South Carolina. They grew up playing on the streets.

Jim McClure, who co-taught with him, reported that Kirkland was raised by a village: If you acted up, the mother next door would discipline you as if you were her own child. The West Side Trail would link those in West End neighborhoods, including residents without transportation, with job opportunities, such as those in York College’s Knowledge Park, now under construction.

Unfortunately, 1960 urban renewal initiatives leveled Kirkland’s old Codorus Street neighborhood. Redlining and other discriminatory government programs had discouraged investment in the neighborhoods. The families were dispersed throughout York and elsewhere. That old neighborhood is marked today by Martin Luther King Jr. Park.

There are four goals of the Codorus Greenway project:

- Reconnect marginalized communities to each other and to economic opportunities.

- Provide accessible and equitable multimodal transportation for those without cars to better access jobs, services, and recreation (27% of households in the neighborhoods don’t have cars).

- Connect to regional active transportation and trail networks, including the Heritage Rail Trail, September 11th National Memorial Trail and East Coast Greenway.

- Boost economic growth and climate change resiliency along the Codorus Creek.

Let’s rewind the clock. How did energy from the creek impact the Civil War?

The nation was engaged in battle for four years (between 1861 and 1865). During that time, soldiers needed protection for all weather patterns, including warmth in the winter. The Union Army turned to York County PA to supply them with one of the sources of their blankets.

The Codorus Woolen Mill was built north of Glenville in 1790. The steady water from the West Branch of Codorus Creek flowed over the waterwheel, spinning and processing the fibers into fabric. It continued operating into the 1900s.

There is no evidence the mill was ever visited, let alone under attack, by the invading Confederates. We know cavalry actively patrolled southern York County during the Gettysburg Campaign. But the horsemen focused their efforts on flour mills not only as sabotage but to forage for their own meals. If the Confederates had known this mill supported the Union military, it could have been set ablaze.

Let’s jump back a few MORE thousand years to the Indigenous Presence

Native Americans lived on this land for thousands of years. In fact, we get the word “Codorus” from Native Americans which means “rapid water.” While we know the most about the Susquehannocks, discoveries of artifacts that pre-date the Susquehannocks have recently been unearthed.

Katherine Sterner, a Towson professor, and 2 archeology students conducted a 5-week field survey. They dug 1.5-foot-wide holes in the farm fields along the south and east branches of Codorus Creek.

Prehistoric settlers would chip away at larger stones as they made tools, leaving behind small flecks of quartz. Archeologists call these artifacts debitage. The researchers shook the soil through the wire screen, scanning for artifacts. This method is called shovel testing, and the debitage isn’t obvious to the untrained eye.

Indigenous peoples followed the west branch of the creek on a footpath called the Monocacy Trail. When white settlers came, they didn’t just pick a random spot to set up their town. Land was a major determinant, but water is arguably even more important.

In Carter and Glossbrenner’s book (1834), they explain that 1729 marked the first time white settlers ventured across the river. According to the authors, John Hendricks and James Hendricks and several others built homes on or near Codorus Creek. This speaks to the importance of this waterway for survival.

Development along the creek banks leads to pollution

Codorus Creek is one of the major waterways through York County. It sustains ecosystems, waters crops, and supports businesses. So many businesses depended on the Codorus that a lawsuit was filed over it.

A York County water company in Hanover started siphoning water from the west branch in 1910. This threatened the livelihoods of three millers in the southwest part of the county. They took the water company to court. To find out what happened, click HERE.

Countless animals, insects, and humans thrived because of it. But its generosity ended up being its demise. Like many other streams, the Codorus became a victim when the businesses and homes built along its banks started dumping.

Dumping was first documented as far back as 1816 – the same year water flowed through wooden pipes installed by the York Water Company. York Water offered fresh water through these wooden pipes laid in the city. We were clearly polluting into the 20th century when reports of sewage and industrial waste darkening the water started to emerge.

The Codorus’ reputation of foul odors and filth earned it the nickname “Inky Stinky.”

One-third of the county’s water drains through it, rendering it susceptible to lazy waste management solutions. It’s simply easier and cheaper to dump waste in a backyard creek than it is to properly process it.

During the 1960s, 22 out of 40 industrial sites dumped directly into the water. In addition to factories and commercial operations, 60% of residents relied on it for their water source and sewage treatment.

In addition to pollution, flooding became an issue

The Codorus has flooded many times. In 1817, ten people died from the rising water. “The Codorus had swollen into a mighty river,” wrote Carter and Glossbrenner. Houses crashed on the current and bridges whipped out like toothpicks. Anywhere from 50 to 100 homes were destroyed.

That wasn’t the first time strange things have floated down the Codorus. Pumpkins in 1784 were torn off the vines and swept downstream until they were scattered across York County close to the river.

Flooding got so dangerous, and costly, that we finally did something in the 1940s. Following the 1933 flood, we built Indian Rock Dam to manage the water flow. This has protected the city during extreme downpours.

Tropic Storm Agnes tested the construction in 1972. Water overflowed the Codorus’s banks in the City of York, despite the Indian Rock Dam reservoir withholding miles of flood water from emptying into the Codorus. This event was considered a 500-year flood when it occurred but would only be considered a 200-year flood today.

Agnes seriously damaged York County. Houses were drenched. Business interrupted. Lives were disrupted. Agnes also damaged the Native American archeological sites in southern YoCo. Listen to Sandra Stockton’s personal accounts of carrying her four kids though the rushing water HERE.

We built Indian Rock Dam to help with flooding, but what did we do for the pollution?

What can a teenager do, actually? Well, a lot it turns out. Conditions improved in 1967 when local high school student Christopher Wickstom, with the Izaak Walton League, to put pressure on the government. The 13,000-signature petition to clean up the waterways convinced Governor Raymond P. Shafer to support the state legislature to clean up the Codorus.

This speaks to the power of one voice who, when organized with some leadership skills, can truly make a difference.

At the time, people claimed “No fish could live in Codorus Creek.” It had become that polluted.

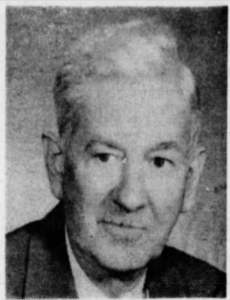

Dr. Robert Denoncourt of York College wanted to find out for himself.

With a team of local educators and students, Denoncourt waded into the Codorus waters at four separate locations spanning from Beaver Street to Spring Grove. They collected specimens from 24 fish species and 21 invertebrate species. They believed the abundance of fish and diversity could make York County a warm water sport fishery. The water wasn’t perfect, but oxygen and acidity levels meant fish could survive.

This pioneering research is believed to be the “first published record of a biological study in Codorus Creek,” according to an article from The York Dispatch. This study would provide a baseline for researchers for the next 50 years.

Denoncourt came under attack when he claimed the Codorus Creek was coming back to life.

Assertions of “A local miracle,” by the York Daily Record (1971) caught the attention of the Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA’s suspicion led to a surveillance and analysis report. The Codorus, the EPA wrote, was still “chemically and bacteriologically polluted.” In fact, the section of creek below the Glatfelter Paper Co. in Spring Grove was “close to biological death,” a representative said at an event at York College.

Denoncourt sat in the audience, listening to the EPA. He didn’t like what he heard.

“He’s wrong,” Denoncourt said. “What we’ve found (in the Codorus) doesn’t indicate a ‘healthy creek,’ but there are considerable fish and insect life there.” The EPA agent countered that more than 100 municipalities and companies dump their waste and raw sewage directly in the Codorus.

Denoncourt did not shrink from the public spotlight, and he actually stepped up his game. Read THIS article to find out what Denoncourt did.

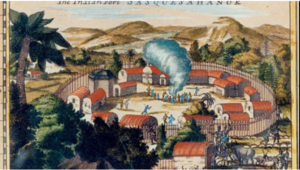

the end of the creek at Codorus Furnace

This furnace is older than the country. It was built in 1765 in Hellam Township and owned by James Smith, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

The location is near the Codorus Creek. Water from the creek powered parts of the furnace via a water wheel and cooled the iron. A race carrying water into the wheel would have run parallel to the road close to the current parking lot.

Cannon balls produced here were used in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. The furnace closed in 1850.

The questions

As this timeline demonstrates, the Codorus Creek played a large role in helping York County develop into the community it is today – some for the good and some for the bad. For a long time, we were willing to sacrifice nature in the name of convenience paired with an attitude of apathy. However, local beautification efforts will give us a chance to do right by the creek. What else can we do to take better care of our ecosystems? What more can we do to help the Codorus recover after centuries of abuse?

Related links and sources: Calling attention to York County’s water pollution through research, activism; Hometown History episode 2.6 – Tropical Storm Agnes’ at 50: When it rained, it poured; Flowing through history: A study of businesses and environmental impacts along the Codorus Creek in York PA; York County Economic Alliance’s Codorus Greenway project.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE