‘When the very stones cry out’

First Presbyterian graveyard

225 E. Market St., York

The situation

In 1965, the Black congregation at Faith Presbyterian Church in York merged with white parishioners at nearby First Presbyterian Church. That merger has been feted as a bright spot in the turbulent 1960s in York County.

The Rev. Guy Dunham, a retired Presbyterian pastor and a leader at First Presbyterian, has looked closely at the congregation’s history.

He has placed that merger in a larger historical backdrop and has found things about the combination that worked – and some things that did not. His guest WitnessingYork.com post, below, lays out these moments, using the church’s cemetery as a thread throughout his essay.

This graveyard tells the story of its church’s 260-year historic

relationship with race and racial justice.

On Sunday, June 19, 2022, a Presbyterian congregation, whose history spans more than 260 years, will gather to worship and celebrate the 70-year-old history and legacy of a Black Presbyterian congregation with which it merged during the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. Such a union during that period was rare, particularly in light of the fact that it was said that theirs was one of only three similar interracial church mergers in the denomination (if not all denominations nationally) in that tumultuous decade. But what makes this gathering of Black and white congregants even more unusual is the fact that the history of First Presbyterian Church in York is almost a microcosm of the nation’s history itself. And strangely enough, it is the church graveyard that, in part, reflects that remarkable history.

Revolutionary beginnings

Only a few blocks from Continental Square, the plot of land on which the sprawling sanctuary, chapel and large education wing are located was sold directly to a few of the congregation’s founders in 1784 by the heirs of William Penn. The agreement stated that a plot of land, transferred at the price of five shillings, was purchased “in trust,” and to be used “as a site for a House of Religious Worship and Burial Place, for the use of English Presbyterians, and their successors, in and near the town of York” at the intersection of High (now Market) and Queen streets.

Among the three Scots-Irish Presbyterians who purchased the land were a wealthy town merchant, George Irwin, a military colonel who served in the Revolutionary War; William Scott; and one of the major surveyors, Archibald McClean, who had assisted Mason and Dixon in establishing the line now forever symbolic of the border between the North and the South, between freedom and slavery. Ironically perhaps, is the fact that two of the three men, Irwin and McClean, enslaved people. Records from 1783 indicate that Scots-Irish settlers owned 59 percent of the enslaved people in York County, although they themselves comprised only 32 percent of the total number of households.

Unlike the buildings that take up most of the land, a modest but stately graveyard, located on either side of the sanctuary, belies the historical significance of those who rest there. In addition to George Irwin and his wife, who actually lie beneath the sanctuary, is another Scots-Irish church founder, James Smith, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Smith is not known to have been an enslaver. Yet a few feet away lies the gravesite of still another church founder of Scots-Irish descent, Lt. Colonel David Grier, Revolutionary War hero, who later served in the newly formed Pennsylvania legislature and was the first to be buried in the graveyard in 1790. He also was an enslaver.

If the graveyard story ended with these individuals, its implications would have sufficed. But it does not, for only four or five steps from where Grier lies is the gravesite of his daughter and son-in-law, Charles A. Barnitz. An attorney by profession who once served in the U. S. House of Representatives, he was a strong proponent of abolition. In cooperation with two Black employees who worked at his stately York mansion, Springdale, Barnitz participated in securing the clandestine transportation of freedom-seeking slaves, many who had crossed that famous Mason-Dixon Line only 17 miles south of York. In other words, he was an Underground Railroad “conductor.”

Not far from his grave, one can see a large headstone with the names of Samuel and Isabel Small. Almost equally distant in the other direction, near to that of James Smith, are the headstones of Phillip Albright and Sarah Latimer Small. Philip and Samuel were brothers, internationally known industrialists of the 1800s, trustee and elder of the congregation respectively, and, most likely, held anti-slavery convictions.

Although not buried in the church graveyard, cousin David Etter Small, another church elder and internationally renowned railroad car builder with business partner Charles Billmeyer, was adamant in his anti-slavery convictions and was suspected by some of including secret compartments in their railroad cars to transport freedom-seekers. Abolition was not a popular position to hold in York County, much less among one’s own expansive Small family. Their cousin, David Small owned one of the local newspapers and often publicly espoused anti-abolition, even racist, sentiments.

Like the newspaper owner, York County was largely in favor of maintaining the status quo in regard to the slavery issue and was famously known as being among only a handful of counties in Pennsylvania to not vote for Abraham Lincoln … twice. At one time, York achieved the dubious honor of being referred to as the “most southern town north of the Mason-Dixon Line.” Other historians have said that York could never quite decide if it was “north or south,” even though its soldiers supported the Union during the Civil War.

Abolitionist Pastors abound

Throughout the 19th century, First Presbyterian Church (a.k.a. English Presbyterian) was led by a succession of pastors with moderate to strong anti-slavery convictions. One pastor held to them so tenaciously that he got into a notorious fist fight with a Southern sympathizer on Market Street and had to be bailed out of jail by Philip A. Small so that he could return to the pulpit the next morning. Two other anti-slavery pastors are buried in the church’s graveyard. Called in 1793 as the congregation’s first pastor, Scots-Irish immigrant the Rev. Robert Cathcart, having the longest tenure, is buried with his wife near Philip A. Small’s family plot. Cathcart, labeled by some as a “conservative progressive” for his time, was known for publicly defending the Rev. Dr. Albert Barnes during Barnes’ 1835 heresy trial held by the Presbyterian synod in the sanctuary of First Presbyterian at the invitation of Cathcart. As a “New School” adherent – as was Cathcart – Barnes’ convictions included strong abolitionist views.

The other pastor, the Rev. Dr. Henry E. Niles, had the second-longest tenure having served from 1865 to his death in 1900. Niles had the unfortunate challenge of being installed as pastor on Easter Day in a black-draped sanctuary only two days after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Interestingly, for over two decades Niles would serve as a trustee of the university that was named after the slain president, Lincoln University, the first degree-granting academic institution in the nation, among Historically Black Colleges and Universities

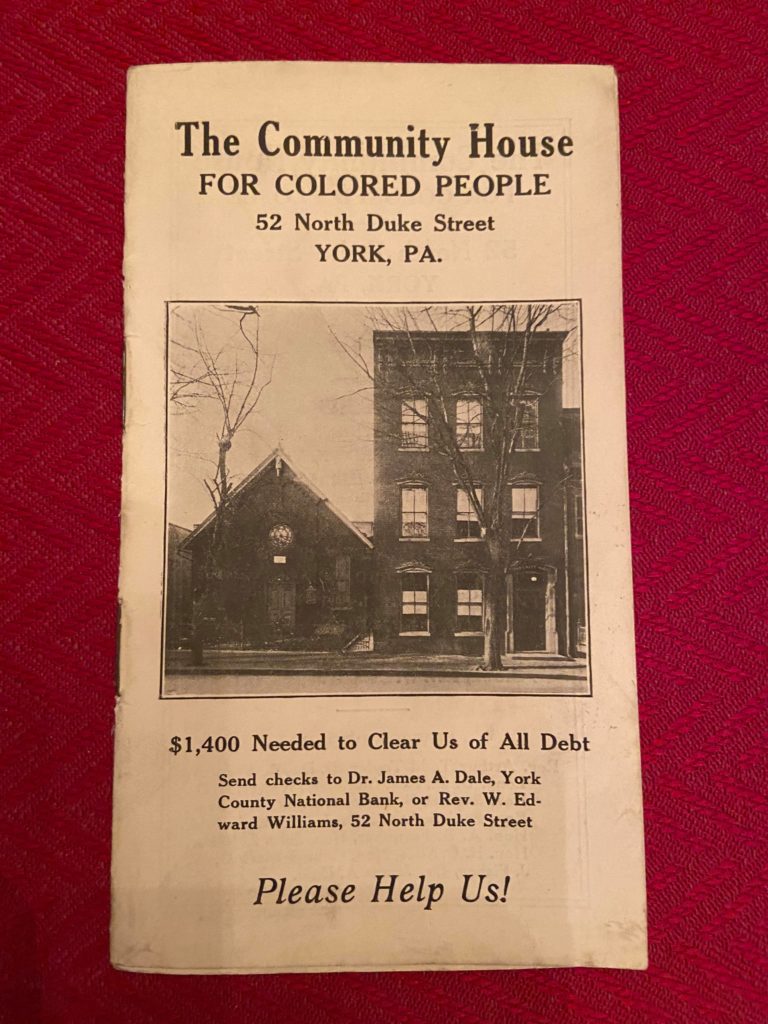

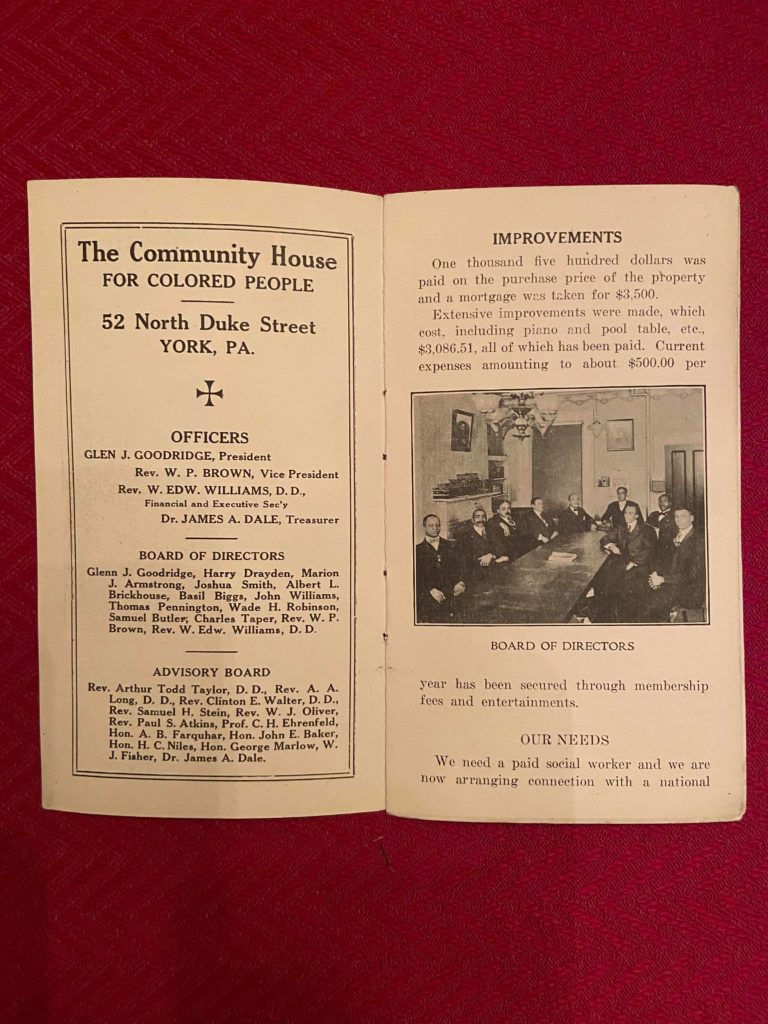

A Black Presbyterian congregation is birthed

In 1895 Henry E. Niles would present to the Westminster Presbytery a petition from 70 signers requesting that it establish them as what would become the first (and only) Black Presbyterian Church in York. The Presbytery concurred and Faith Presbyterian Church was established. Its building, purchased in 1894 at the encouragement of Samuel Small, son of Phillip A. Small, was located only one long block from First Presbyterian. When the mortgage for the North Duke Street building was burned eight years later on June 19, 1902, Small was credited with paying off the balance and thereby relieving the heavy financial burden of the fledgling congregation. The congregation would become known not only for its service to the Black community but for its pastors who were often strong civil rights activists during the early- to mid-1900s.

Among them was the Rev. Thomas E. Montouth, an early champion of civil rights in York and one of the founders of the now nationally acclaimed York Crispus Attucks Association. One of his successors as pastor at Faith, the Rev. J. Jerome Cooper, would eventually serve as president of the Crispus Attucks board for three years in the early 1960s. When Montouth died in 1977, he was buried in North York’s historic Lebanon Cemetery, established in 1872 when Black residents were not permitted to be buried alongside whites.

In that same cemetery, numerous charter and other members of Faith Presbyterian Church had been laid to rest. Among them were Glenalvin Goodridge, Jr., the grandson of William C. Goodridge, born enslaved and later a successful York Black businessman, whose house served as part of the Underground Railroad. Glenalvin was the son and namesake of an acclaimed pioneering Black photographer whose work has been acquired by the Smithsonian. Next to Glenalvin lies his mother, Rhoda, who was from the Grey family and whose house, also a refuge for freedom seekers, was located just a block away from the Goodridges.

Being a railcar owner himself, it would not be a stretch to believe that William Goodridge, and even the Greys, were kindred spirits of the anti-slavery railcar builder David E. Small, as well as his cousins, Philip and Samuel. The homes of each of the Smalls were located only a few blocks away from that of Goodridge, whose East Philadelphia Street house now serves as the Goodridge Freedom Center and sits just around the corner from the former site of Faith Presbyterian Church.

Until recently Lebanon Cemetery, located several blocks north of First Presbyterian Church, had suffered from serious neglect. Recent efforts by a volunteer organization, Friends of Lebanon Cemetery, have cleared gravesites of weeds and debris, located unmarked graves, and cleaned or reset sunken headstones often buried under as much as six inches or more of dirt and grass. Over the past year, members of First Presbyterian have participated in the effort to restore the cemetery.

After Henry E. Niles’ death in 1900 – and in the midst of the unabashed practice of Jim Crow laws throughout York County – the voice of racial justice fell strangely silent in the pulpit and halls of First Presbyterian Church. While the congregation continued to grow in numbers and in prestige, the cries for racial justice, by which its congregation and pastors had been known in the previous century faded, and a long tradition of speaking out on civil rights was left to its Black sister congregation to carry the burden alone.

The strange silence at First Presbyterian is broken

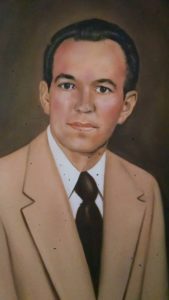

That silence in one of the most prominent, affluent, and influential congregations in York was broken when a young pastor arrived in the same year as the landmark Brown vs Board of Education decision in 1954. Already possessing preaching skills beyond his thirty years, the Rev. Dr. Ernest T. Campbell was committed to bringing his blend of “evangelical” theology and racial justice convictions into the pulpit and eventually to radio. Years later, “Ernie” Campbell would go on to lead the renowned Riverside Drive Church in Manhattan, New York City.

But as far as any member at First Presbyterian Church can recall, Campbell’s consistent plea for an end to racial discrimination and equality for all Blacks met, at best, a lukewarm reception from the largely middle and upper-class members in the pews. Nonetheless, there can be no doubt that the unseen effects of his persistent message contributed to a greater receptivity, albeit also meeting with some serious resistance, to the historic merger of Faith and First Presbyterian Churches three years after his departure in 1962.

In 1963, two pastoral calls took place that would impact both Faith and First Presbyterian churches. A year after Campbell took a call in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Faith Presbyterian Church’s beloved pastor since 1956, J. Jerome Cooper, accepted a call to the 700-member Berean Presbyterian Church, a historic Black congregation in Philadelphia. At that same January 1963 presbytery meeting in which Cooper’s call was approved, another action was taken to grant permission for Rev. Dr. Richard Oman to leave Oxford Presbyterian Church in southeastern Pennsylvania – once pastored by one of the founders of Lincoln University, the Rev. John Dickey – and to accept a call to the First Presbyterian Church of York.

The difficult beginnings of a merger

In late 1963, twenty-six-year-old Douglas G. Parks graduated from Union Seminary in New York City. He also was a civil rights activist, who during the summer before had marched to desegregate Charleston, S.C. and subsequently had been befriended by the Rev Dr. Martin Luther King. At their request, he sat down with denominational officials of the United Presbyterian Church in its headquarters at 475 Riverside Drive in New York City. They told the white seminary graduate of a struggling Black congregation in York for which the denomination could no longer afford to continue providing financial support. Would he consider going there as a supply pastor in order to do a sociological study of the community, consult with other Presbyterian congregations and ascertain whether or not a merger with one of them would be feasible?

After an encouraging conversation with King, Parks accepted the challenge and was readily approved by Faith Presbyterian’s church elders to serve as their supply pastor and for the expressed purpose of exploring the possibility of a merger with another Presbyterian congregation. Perhaps unknown to Parks, his predecessor Jerome Cooper had, in his 1960 pastor’s report to the congregation, already broached the subject of Faith merging with Calvary Presbyterian, another struggling church in York, after engaging in conversations with Calvary’s pastor and a Synod executive. Incidentally, Calvary had been founded by Samuel Small and his uncle and aunt, Samuel and Isabel Small in 1883 as a mission outreach of First Presbyterian. But after consulting with seven other churches and their pastors, including Calvary, Parks came to the conclusion that First Presbyterian Church was the only one truly open to discussing a possible merger with the Black congregation.

Before those conversations would begin, Parks was contacted by Dr. King and asked if he would travel to Selma, Alabama to assist an equally young John Lewis in their voter registration efforts. The Session at Faith readily approved his trip with their blessing. It was there in Selma on March 7, 1965, that Parks would find himself on the Edmund Pettus Bridge during what has become known as Bloody Sunday.

Surviving the horrific event, and at King’s request, Parks called all his contacts with various denominational headquarters, the National Council of Churches, as well as the three major TV networks, pleading for additional protestors to join them for the next march. Eventually, the youthful pastor accompanied King and Lewis to Montgomery, and then returned to York even more committed to the potential merger that eventually would take place. Now in his early 80s, Doug Parks is the only living pastor of Faith Presbyterian Church and presently resides with his wife in California.

During the ensuing months, two teams of members representing each congregation met to discuss possible terms of a merger, timelines, etc. However, even before Parks had returned from Selma, unfounded rumors had already begun to swirl around the white congregation, claiming that a small group with a hidden agenda was behind the idea of a merger. On Sunday, March 22, 1965, Richard Oman took to the First Presbyterian pulpit, setting aside his Lenten sermon and delivering his well-known message, “The Anatomy of a Rumor.”

While most members at First Presbyterian were open to the possibility of uniting with their Black sister congregation, continual resistance coming from some very influential members put Oman’s pastoral skills to the test. Tempers flared in one meeting of the congregation, with applause erupting from each faction when their position on the potential merger was voiced. Angry letters with racist overtones were sent to the pastor and session. Some members expressed fears that healing might no longer be possible.

A near collapse of the session’s support of the merger proposal and terms was avoided when, once again, the firmly committed pastor of First Presbyterian challenged the elders in regard to their responsibilities as Christian leaders. The session subsequently approved the recommendation that a special congregational meeting be held. And so, on Oct. 27, 1965, each congregation met separately to discuss and act upon the motion to merge. With twenty-six members in attendance at Faith Presbyterian, 24 voted in favor and 2 abstained. With over three hundred in attendance at First Presbyterian, 229 approved the motion and 108 voted against.

Two months later, on Sunday, Dec. 21, 1965, Faith Presbyterian held its last worship in its sanctuary at 50 North Duke Street. Three days after, with a Christmas Eve crowd overflowing in the 1800s-style sanctuary, the two York congregations become one. A total of 91 members from Faith agreed to have their membership transferred to the rolls of First Presbyterian.

The witness

The proverbial happy ending?

By all accounts, the merger went smoothly. Only a few members from each congregation chose to leave. Some from Faith returned to Black congregations more aligned with their childhood experience or where other relatives already attended. And according to church records, very few members of First Presbyterian actually chose to transfer to other congregations, contrary to what had been predicted by opponents.

From the outside, the story appears to have a happy, Hallmark-type ending: a growing romance nearly ruined is suddenly saved at the last minute and all live happily ever after, or so the script implies. However, recent research into Faith Presbyterian’s history, coupled with open and candid conversations about the merger and the decades following, have provided some crucial revelations. They are critical for a congregation that is trying to become authentically multiracial, even in the midst of a polarized social climate where race and civil rights continue to dominate the public discourse and growing movements such as White Christian Nationalism are gaining more influence.

Leading up to June 19, 2022

Over the past few months during Sunday worship, the First Presbyterian congregation has viewed a series of five-minute videos which briefly cover important aspects of Faith Presbyterian’s history. Even former members of Faith, and their descendants, have discovered facts about the congregation and its pastors of which they had been unaware. The Racial Justice Task Force, formed after the murder of George Floyd, has provided opportunities for Black members to share candidly their own experiences of racism in daily life of which their white counterparts had been unaware.

All of this has proven to be somewhat of a two-edged sword for First Presbyterian Church.

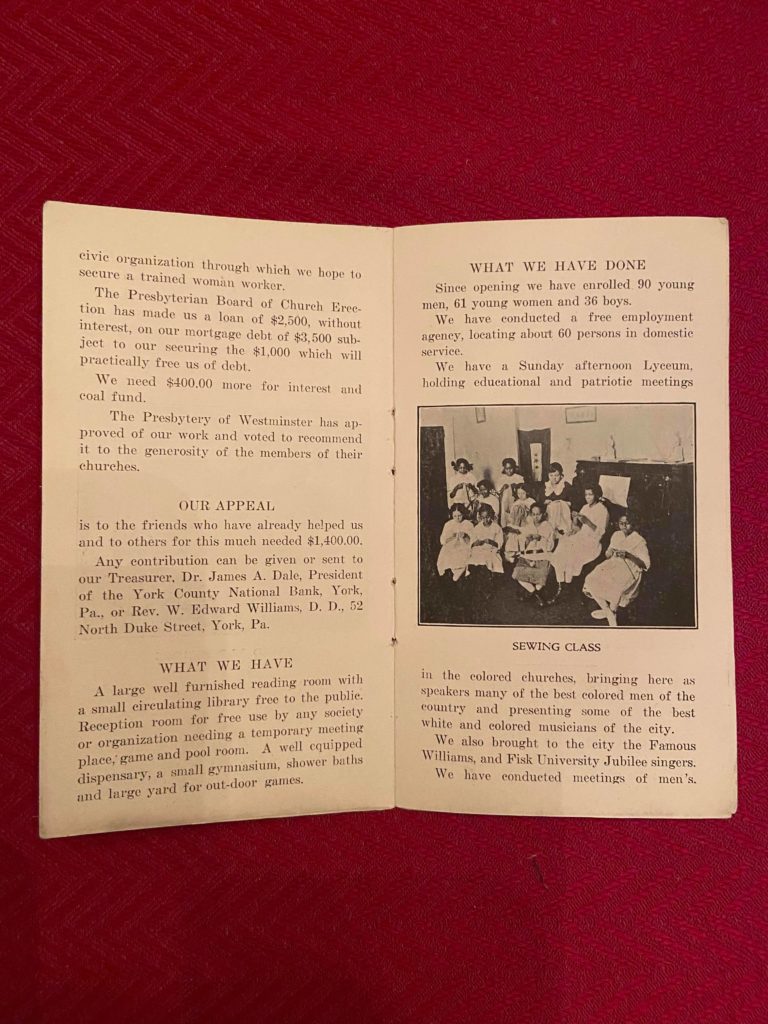

On one hand, church members have learned that for years the Black congregation was anything but a small, struggling church, but rather during its 70-year history, it produced several of the most influential movers and shakers in the Black community, in York, and far beyond. In addition, its Community House was a forerunner of the highly acclaimed York Crispus Attucks Community Center. As a result, First Presbyterian has appropriately been recognizing and celebrating Faith Presbyterian’s rich legacy.

On the other hand, revisiting Faith’s past, as well as the subsequent merger, has provided opportunities for more forthright discourse – conversations about First Presbyterian’s unawareness of the grief experienced by members of Faith as their congregation was essentially disbanded, their church name retired, their sanctuary sold and demolished and the proceeds from the sale apparently absorbed into the church’s assets.

In addition, the congregation has had to acknowledge that after the fervor of the merger subsided, the still predominately white congregation missed opportunities for more intentionally including Black members in decision making, of increasing an awareness among themselves of using racially insensitive language and stereotypes and, up until only recently, of failing to call Black pastors or other full-time professionals to serve on staff.

In 2015, during the 250th anniversary celebration of the congregation’s founding former senior pastor, the Rev Dr. John Galloway, admitted that his only regret was that he did not encourage the congregation to call a Black associate pastor during his tenure in the 1970s. Looking back, some are now discovering that the ill effects of these missteps resulted in several former Faith members transferring to other Black congregations only a few years after the merger. Now, fifty years later, the congregation presently employs two Black full-time program staff. In July, a third person of color will assume the important full-time position of Director of Worship and Music.

Celebrating Faith Sunday

And so, on June 19, 2022, exactly 125 years after Faith Presbyterian’s burning of their sanctuary mortgage, members of First Presbyterian Church will gather to worship as well as to celebrate and lament.

Together, Black and white, they will celebrate the life and contributions of a Black sister congregation.

Together, Black and white, they will lament those ways in which their Christian sisters and brothers had fallen short in regard to standing with them in their quest for racial justice.

And finally, Black and white – all races, in fact – they will once again gather around the familiar table of grace-filled reconciliation, resolving to do better in not only following the example of Christ himself, but also that of those champions of racial justice whose very headstones in the graveyard outside their sanctuary walls remind them they must go and do likewise.

The questions

During the merger, angry letters with racist overtones were sent to the pastor. Have you ever encountered opposition when you followed your own moral compass? If you were the pastor who promoted this merger, following what you knew to be right, how would you respond to aggressive letters like this?

Related links and sources: Witnessing York: How York’s Faith Presbyterian and First Presbyterian merged (witnessingyork.com); York’s Faith and First churches showed special faith in merger (ydr.com); A Black pastor’s 1916 message to York on equality is still relevant today (ydr.com); The bulldozer and wrecking ball took many historic York properties (ydr.com). James McClure’s “Almost Forgotten.” Community House pictures and booklet, Gregg Poff; Other photos, YDR files.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: Black & Latino history studies: Logjam breaks in York County - Witnessing York