Class division, even in death

The unmarked graves of forgotten Yorkers

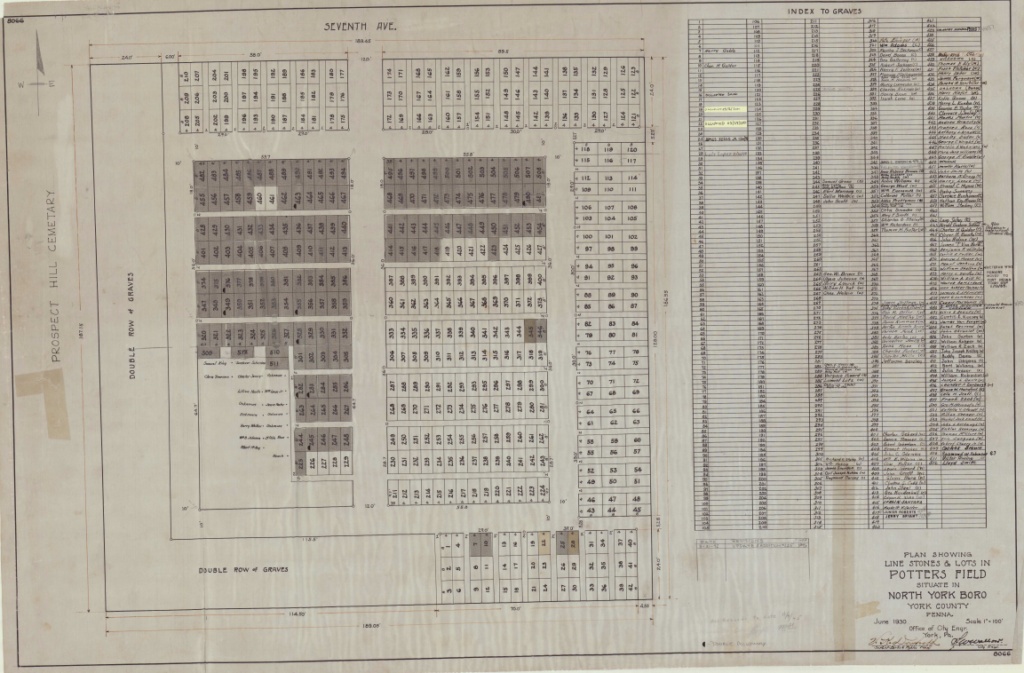

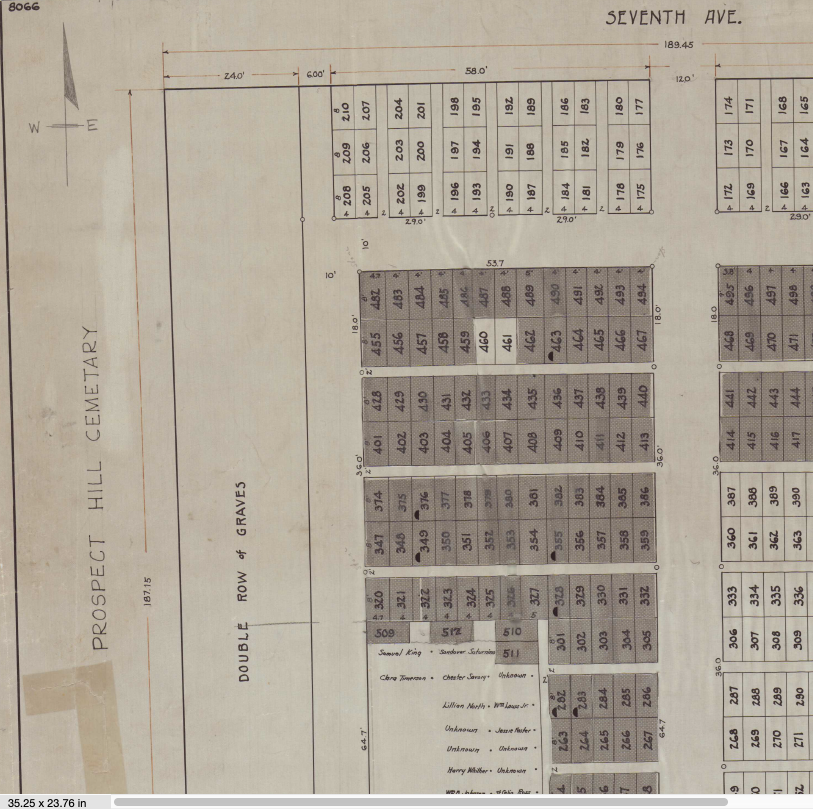

Schley Alley and W. 7th Ave., North York

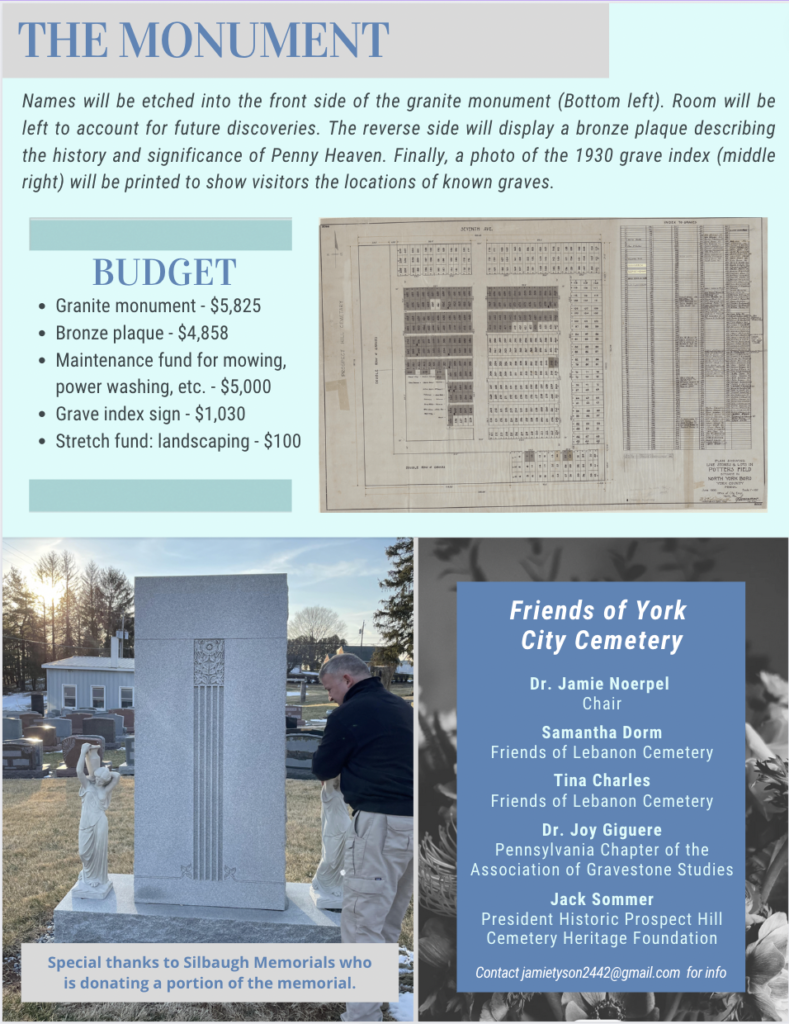

Jamie and the Friends of York City Cemetery are raising money to install a permanent memorial. If you’d like to contribute, visit Preservation PA’s Donation page.

The situation

In death as in life, we overtly signal our class. By the cars we drive, square-feet of our homes and brand names we don – our status radiates from us. The same goes for our cemeteries.

For decades, York County used a field located on West College Avenue between South Beaver Street and South Cherry Lane to bury people.

Michael Shanabrook, a city planning engineer from 1977 to 2002, says that if an individual had no family, no financial means, or was unidentified, they would be interned in the potter’s field. The city physician would coordinate the paperwork, and the engineer would locate and identify the burial site. Then, a public works crew dug and filled in the grave.

Today, the land is a parking lot for St. Patrick’s Church.

In 1897, the city moved the bodies to another field located next to Prospect Hill Cemetery along Schley Alley.

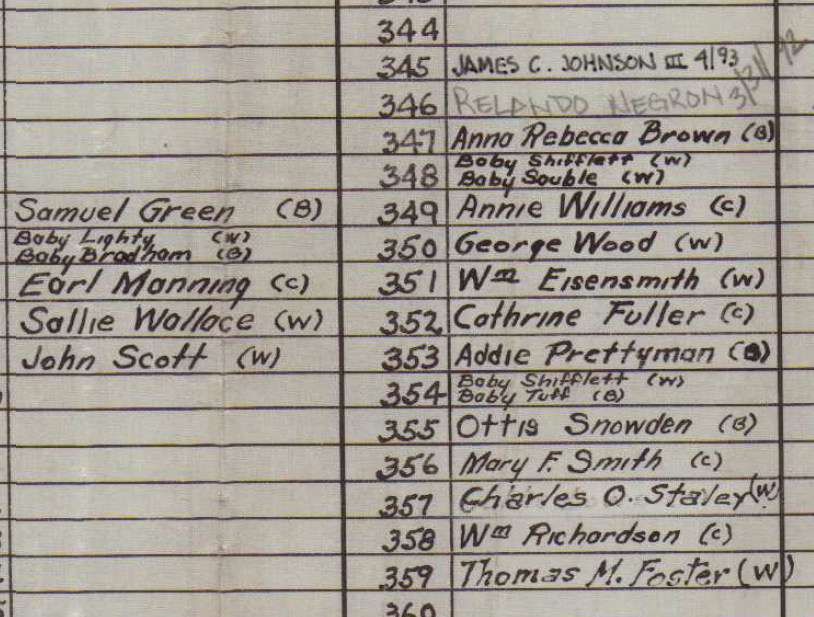

Most of the 600+ bodies in that hallowed ground are still unidentified.

The witness

The burial practices in York County reflect broader values. In short, how we treat our dead says a lot about us.

The city cemetery to the east of Prospect Hill Cemetery served as a de facto cemetery for the unknown or poor people.

We don’t know much about those buried in the City Cemetery, so we look to past practices nationally to provide context for potter’s fields.

Across the country, individuals who a society deemed worthless or illegitimate were sometimes abandoned, covering up the bodies while simultaneously concealing the town’s “ills.” Examples include non-Christians, un-wed mothers, criminals, babies, people who were not baptized, and others wrongly labeled “morally loose” or “infirmed.” Again, we can’t say for sure why people were buried in the City Cemetery, just that they were unknown or couldn’t afford a burial plot.

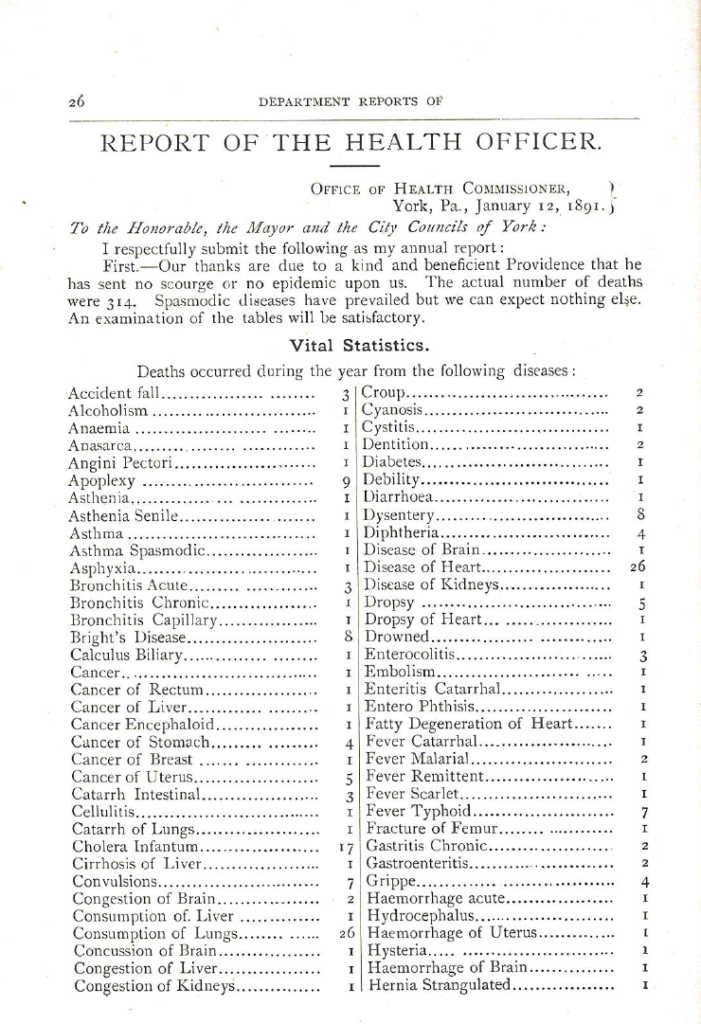

Ami L. Miller, the Executive Assistant for Prospect Hill Cemetery, believes the majority of people interred died from smallpox.

When looking at the index of names, we know that Blacks and whites were buried together decades ago. The deceased often were separated by race then, but that didn’t matter when it came to the unidentifiable or impoverished.

Tina Charles, volunteer for the Friends of Lebanon Cemetery, tells us that before Blacks were frequently buried in potter’s field. When the bodies were moved to the new property, known individuals were interred to Lebanon Cemetery. Those unidentified moved with the others to the new Potter’s Field.

Historical moments, such as the transferring of bodies to North York, gives us a glimpse into the thinking of our forebears. The unmarked graves send us a clear message that their names mean little, buried anonymously in a remote area and segregated from people who paid for their plots and were respected by the community.

By the 1800s in America, funeral practices increased in cost. People desired more elaborate going out parties such as interior casket trimmings and more expensive outfits for people both in and out of the coffins. Embalming grew into a common practice after the Civil War as well.

The commodification of the funeral industry exposed the class divide more than ever.

As a response to the growing class division, the use of potter’s fields increased. This was also the time of “ugly laws.” These were pieces of legislation directed toward segregating people considered unsightly due to war injuries, birth defects, or industrial accidents. State lawmakers all over the country, including Pennsylvania, used the legal system to erase people who were disabled from sight.

According to the Encyclopedia of Disability, Chicago passed the first ugly law, forbidding “any person, who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or deformed in anyway, so as to be unsightly or disgusting object, to expose himself in public view.” Thankfully, these laws were removed from the books.

At a minimum, people in poverty were assured a final resting place, but the way we treated individuals sent to the potter’s field reveals how we think of those lacking identity.

Public beliefs surrounding causes of poverty have changed over time. Andrew Nelson in “Finding Those Once Lost: The Analysis of the Potter’s Field at Woodland Cemetery, London, ON” wrote that reasons for poverty fell into three broad categories:

- Individual explanations such as personal choices or character traits

- Structural explanations such as societal norms, laws, and systems

- Fatalistic explanations that are uncontrollable such as bad luck or accidents.

At the time, Americans mostly attributed poverty to the first reason — an individual’s laziness. Many would argue this plays a factor, but today we are starting to look at poverty differently.

People from lower-income backgrounds are still marginalized, but there is more acceptance, including here in York. Programs, initiatives, and philanthropic endeavors are working to change the idea that poverty is a reflection of circumstances, not poor morals.

Project Penny Heaven – Goal: $20,000

Poetry and poverty

Even though many during the 19th century in history – and some today – ostracized the poor, others sympathized with those sent to potter’s fields. Take Bertha B. Herring of Hanover for example. In a 1895 poetry contest published in The Gazette, she wrote a poem called “The Potter’s Field,” earning second honorable mention:

In the midst of the city’s mirth Lie in this neglected spot of earth God’s poor; friendless, unclaimed, or unknown They rest here in peace alone.

Ah! judge them now, they’re richer far. Than richest men, who wear sin’s scar And have not learned to know God’s love, These own a home with Him, above.

Here a tiny mount - a little flower, Torn from the parent stem, but far Fairer to one month’s bleeding heart, Than all the buds that bloom apart.

Tread softly! Here there lies a gentle maid, Sinful you called her; true she may have strayed In evil hours, when sin’s mad incense wreathed, But was recalled by that last prayer she breathed.

A mother here - her mission just begun, Gone from her little one - too weary to keep on; O mothers in your home; of joy and ease, Do your prayers e’er rise for such as these?

Here an aged head - gray, weather-stained, and old, Died alone, unnoticed in the darkness, still and cold; No little prattlers ever gathered round her knee, Her life knew naught by want and endless misery.

This little poem, has a mission if unfurled, There are many poor in this bright, busy world. Go cure by sympathy the gnawing pain, And banish sin - our Nature’s darkest stain.

The North York City Cemetery permanently marginalized the poor by finalizing their place in society — on the outskirts, unidentified and forgotten. By studying York’s potter’s field, we reveal the expression of class privilege, even in death.

The Question

We can look at this potter’s field to explore what the rest of us take for granted — that we’ll be taken care of after death.

What do we “owe” the people buried in North York’s City Cemetery? Should we dedicate a proper sign, listing the names we know? If so, what would go on the sign or monument?

Related links and sources: “Finding Those Once Lost: The Analysis of the Potter’s Field at Woodland Cemetery, London, ON” by Andrew J. Nelson; “York’s Potter’s Field exhumations center of early dispute about disease” by Jim McClure; Jamie Kinsley Photos of cemetery; Mike Shanabrook provided health and burial records.

Just around the corner from the City Cemetery is a Vietnamese Church and the Rivera House.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: It's more than a grassy field, City Cemetery bears 800 unmarked graves - Wandering in York County

Pingback: Hometown History - Explore people, places and issues - Witnessing York

Pingback: Reading tombs, Part 1: How Wildasin Cemetery's gravestones reveal much more than names and dates - Wandering in York County

Pingback: Reading tombs: Symbolic iconography on York County's gravestones, Part 2 - Wandering in York County

Pingback: Penny Heaven, gravediggers and chickens

Pingback: Around York County - Doing do-it-yourself urbanism - Witnessing York

Pingback: William Shelton received the recognition he deserved - when will the rest of Penny Heaven's inhabitants get theirs?