Early photography, Underground Railroad intersect here

Goodridge Freedom Center

123 E. Philadelphia Street, York, Pa.

The situation

Glenalvin J. Goodridge started his career as a teacher in York’s Black school, but his diligence as a self-taught student of photography gained him skills that made an impact on local and American history.

Glen, as he was known, adopted photography in its infancy and grew with it. Other people in York engaged with this new technology and most gave up. But Goodridge persisted, meeting the challenges of adapting to changes in his field. Initially, he made his images using a chemical solution on copper (daguerreotypes) and then glass (ambrotypes).

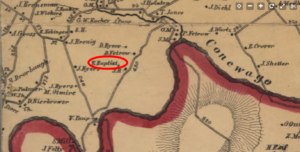

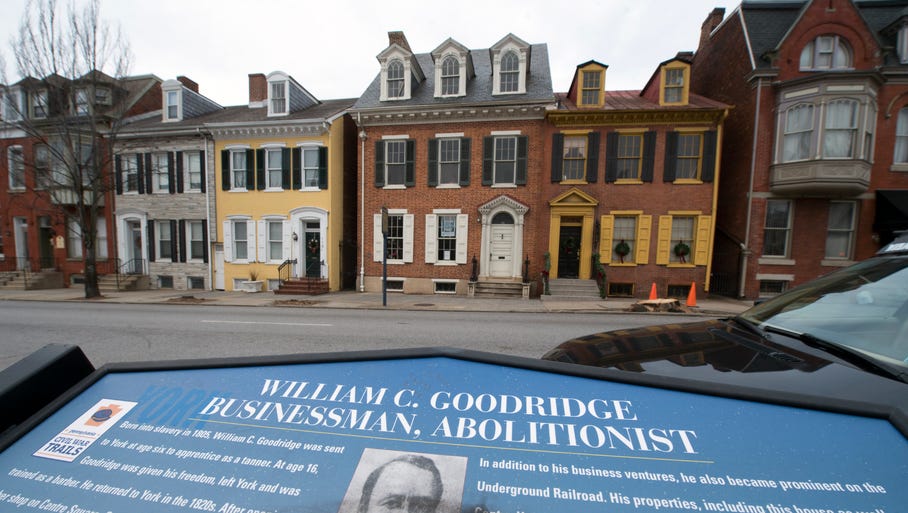

His studio was located in several places around York, including a sunny northwest room in his father’s 123 E. Philadelphia Street townhouse. His father was the noted William C. Goodridge, formerly enslaved and later a successful York businessman.

In 1862, the shutter on Glen’s burgeoning photographic career shut and would never reopen.

He was convicted of rape, largely on the word of a woman who was in his studio for a portrait. His studio then operated in the Hartman building, standing today on Continental Square’s southeast corner. He was sentenced to five years in Eastern Penitentiary in Philadelphia.

His influential father did not give up on his jailed son. He led a community campaign to petition Republican Gov. Andrew G. Curtin for Goodridge’s release.

He and other significant community supporters argued:

The alleged victim waited three months after the attack to report it. Goodridge produced a credible alibi. The jury took 20 hours to reach a verdict, a long period of deliberation. And the conviction would not have occurred if the defendant were white and a Democrat (the majority party in York County.) This campaign took place in the heart of the Civil War, interrupted by York’s surrender to the Confederates and the enemy’s subsequent occupation of York.

The lobbying in support of Glenalvin highlighted two of York County’s pre-Civil War weaknesses: injustice toward Blacks and support of the anti-Lincoln political party – the Peace Democrats – that opposed the war and thus backed the retention of slavery in the South.

The York support moved Curtin to action. He pardoned Goodridge after two years in prison. But there was a big, disturbing condition. Glenalvin must leave Pennsylvania, which he did in 1865.

The incident cost Glenalvin his life. While detained, he contracted tuberculosis. He was released in broken health and died in Minneapolis in 1867.

A career ended, a life lost, a family disrupted, but a body of work that would be remembered.

And feted 150 years later.

An early boost to memory of his work came in 1999 when John V. Jezierski published “Enterprising Images,” a work that documented the life and times of father and mother, William C. and Evalina Goodridge, and Glenalvin and his two photographer brothers, Wallace and William O.

That work placed Glenavlin Goodridge on a short list of accomplished early American photographers.

Recently, the Smithsonian punctuated the legacy of Goodridge work with an exclamation point, acquiring 40 pieces of artwork by Goodridge and two other pioneering Black photographers. Their work, part of the Larry J. West Collection, will be the centerpiece of the Smithsonian’s new early American photography gallery.

“The theme of the gallery is the democratization of portraiture and will include works by non-white and women photographers and portraits of subjects across racial and class identities,” Smithsonian magazine reports.

Glenalvin Goodridge’s life is full of lessons: creativity, persistence, tragedy and redemption.

For more about the Goodridge family and that Smithsonian acquisition, please see: Glenalvin Goodridge, pioneering photographer.

The witness

You could call it a museum within a museum.

The Glenalvin J. Goodridge Photographic Gallery Reproduction forms an intriguing crossroads of several pieces of our past: early American photography, black-operated photo businesses and other 19th-century enterprises, local black history and the Underground Railroad.

Glenalvin Goodridge is at the center of many of these themes.

He opened his first photo studio at the age of 18 in 1847, in one of his father’s businesses, and later operated his studio out of the Goodridge residence on East Philadelphia Street. At that time, that house, now the Goodridge Freedom Center, served as the intersection of early photography and the Underground Railroad.

Several years ago, Larry J. West, Grant R. Romer and Joe Shane made these connections and have brought their avocation for daguerreotypes and other early photographic forms to the Goodridge House.

The result is the Glenalvin Goodridge exhibit – this museum within a museum.

Here are seven points about early photography and Glenalvin Goodridge’s life and times, courtesy of presentations from these three curators and John Vincent Jezierski’s authoritative “Enterprising Images, The Goodridge Brothers, African American Photographers, 1847-1922.”

1. John Jezierski calls the Goodridge family – Glen and his two brothers, Wallace and William O. – one of America’s first families of photography. Goodridge studios in York and, later, in East Saginaw, Mich., operated for 75 years – until Wallace shut down the Saginaw studio in 1922. Commercial photography was about 10 years old when Glen opened the first Goodridge studio, producing daguerreotypes. Louis Daguerre generally is associated with a commercial enterprise that produced images bearing his name in the late 1830s.

2. In York, Glen operated his studio in several locations, including his father’s five-story Centre Square Emporium and the 123 E. Philadelphia St. home of his father. Interestingly, a later York landlord, John Hartman, reportedly built his Centre Square building taller than William C. Goodridge’s five-story business diagonally across the square. According to a letter in a York County History Center file, he reportedly said (with racial epithets) that he would not let a Black man construct a taller building. Hartman’s building, which has had floors added and subtracted over the years, stands today on the southeast corner of the square. Goodridge’s Emporium no longer stands. The Hartman building is the place in which the incident leading to Glen’s rape conviction took place.

3. Glen worked with the various kinds of photographic technology of the day – from daguerreotypes to ambrotypes. Customers found all kinds of uses for their new likenesses – their actual images not previously fixed in time. For example, people would display their photographs in wearable jewelry.

4. Glen also was a teacher at the “Colored High School” in York. Interestingly, another black teacher at that school in that era, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, is known to a national audience today. Through her poetry and other writings, Harper became known as an abolitionist and suffragist in her long life that spanned from 1825 to 1911.

5. Glen Goodridge left York in 1865 to join his brothers in their Michigan photographic business. John Jezierski writes that Glen died in Minneapolis in 1867 from tuberculosis, contracted during his incarceration in Eastern State Penitentiary. He had been sentenced on what turned out to be trumped-up rape charges and released early. Larry West has introduced a theory as to Goodridge’s cause of death. Many early photographers died at a young age from lung ailments stemming from the breathing of mercury vapors and other chemical fumes inherent in photo processing of the day.

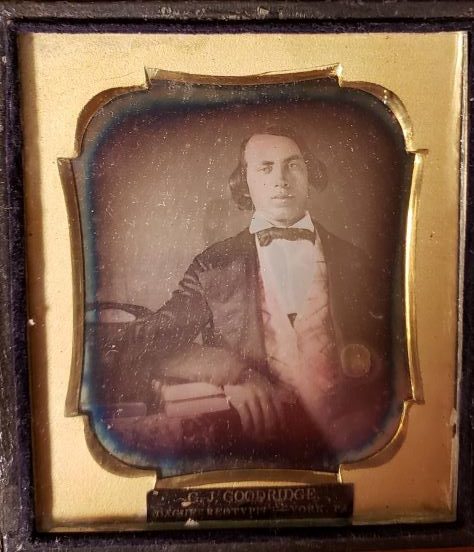

6. Interestingly, despite all this photographic equipment and prowess, only one known photograph of William C. Goodridge exists. No photographs proven to be of Glen Goodridge exist. In his book, Jezierski suggests a portrait of a mullato man with a horse in his book might be Glenalvin. “The young man bears a striking resemblance, especially the aquiline nose and high forehead, to his father, William C. Goodridge,” Jezierski writes. See “Enterprise Images, Page 28.”

7. As for the reproduction studio in the Goodridge Freedom Center, curators say that it is the only known daguerreotype display in space where this early form of photography was actually practiced. And they say that Glen was on a short list of entrepreneurs to form early black-operated photo studios in America.

As for Glenalvin Goodridge, Jezierski says: “G.J. Goodridge was not York’s first photographer, but he was the community’s first native son to establish a studio that operated for more than a few weeks or months.”

The questions

When writing stories like this, Jamie and Jim highlight York County’s struggles yet acknowledge redemption within that same story. This tandem – remembering both the hardship and triumph – illuminate the complexities of a single story. In this example, we explore a man who left a lasting legacy through photography. We also recognize the accusations of rape and the racist judicial system.

As educators, writers, researchers, and/or historians, how can we ensure that we explain both sides of the same coin, without over-romanticizing the positives, or exaggerating the negatives?

Related links and sources John V. Jezierski’s “Enterprising Images.” Jezierski’s 1999 work contains a detailed account of the criminal case and imprisonment of Glenalvin Goodridge. James McClure’s “Almost Forgotten”; York Daily Record and York County History Center files. Photos by James McClure, York Daily Record

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE