Ticket to the past’s Unforgettable Journey

The situation

Community engagement specialist Matthew Jackson viewed a new exhibit at Gettysburg’s Civil War-era train station and believes he witnessed the future in engaging museum visitors with history.

The Hanover native believes Gettysburg Foundation’s “Ticket to the Past: Unforgettable Journey” “feels more like a series of face-to-face encounters than a traditional exhibit-to-exhibit museum visit.”

Jackson’s guest column about “Ticket to the Past” follows:

Gettysburg’s first virtual reality experience promises to stretch your imagination, awareness, understanding and empathy — and maybe even fire up your civic conscience, courage and involvement.

There, at 35 Carlisle Street, at the same train station where President Lincoln came to town from Hanover and Hanover Junction (Seven Valleys) on the Hanover Rail Corporation line in November 1863, to deliver the world-famous Gettysburg Address, you come-face-to-face with one of three extraordinary individuals of that era.

Choose either Basil Biggs, described as freedom fighter, facilitator for the fallen, and pursuer of unfinished work; Cornelia Hancock, soldier caregiver, hospital heroine, and dedicated social servant; or Eli Blanchard, teen volunteer, Iron Brigade band member, and amputation assistant.

Through virtual reality goggles, your character tells you his or her story leading up to, during and following the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1-3, 1863.

The Witness

I chose Basil Biggs (1819-1906) – Gettysburg freedman, farmer, teamster (driver of a team of animals), a self-taught horse veterinarian, disinterment/exhumation specialist, civic leader and Underground Railroad conductor – who also has ties to Hanover; a famous, one-of-a-kind photograph; and York County.

The performance by the actor portraying Mr. Biggs was intense and moving.

Biggs, an illiterate freedman born of mixed-race parents in a Quaker settlement in Carroll County, Maryland, lost his mother when he was only four years old.

He was a master multi-tasker, a hard-working jack-of-all-trades. Throughout his life, Dr. Biggs, as he became known, made the best of each situation with relentless energy and perseverance.

Basil and wife Mary Jackson moved their growing family from Baltimore, in a slave state, to the free state of Pennsylvania in 1858 so their children could get an education and grow up in freedom. At that time, Blacks in Maryland — whether free or enslaved — were denied public education.

According to his 1906 obituary, while a tenant farmer at the Crawford Farm in Gettysburg, Biggs was an active agent in the Underground Railroad. According to historian Debra Sandoe McCauslin, Biggs directed freedom seekers to Quaker Edward Mathews’ farm in Biglerville in northern Adams County.

As about 75,000 Confederates invaded Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863, the Biggs family fled northeast to the town of Columbia on the banks of the Susquehanna River.

When the family returned to town after the epic Battle of Gettysburg, the turning point of the Civil War, everything that Biggs owned was pilfered or destroyed except three assets: two horses and a cart. They also returned to find 45 dead Confederates buried in the fields they tended and tilled.

According to the National Park Service, “the Biggs family lost eight cows, seven steers, ten hogs, eight tons of hay, ten crocks of apple butter, sixteen chairs, six beds, and ninety-two acres of crops.”

After the battle, teamster Biggs’ salvaged cart, which could carry up to nine bodies at a time, came in handy as he embarked on a grisly, putrid and daunting endeavor.

Working for Gettysburg merchant Samuel Weaver to disinter more than 3,000 dead Union soldiers from their initial graves and relocate and rebury them in a central spot, Biggs played a major role in the creation of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery.

From October 1863, until March 1864, Biggs made $1.25 for each corpse brought to its final resting place, including hauling Union corpses from Hanover, 14 miles away. As a famous photo from Hanover shows, Biggs hired several Black men from Gettysburg to assist with the job.

Biggs used his earnings to purchase his own farm, the Peter Frey farm, which still stands on Taneytown Road, and about 120 acres of land. His land included the famous copse of trees, known as the high watermark of the Confederacy at Cemetery Ridge, a must-see visit for battlefield tourists.

In 1881, Biggs sold those witness trees and the seven acres around them to the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association for $1,350.

Although Biggs played a prominent role in the creation of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, he and other Blacks, including those 30 local Civil War veterans of the United States Colored Troops, are not buried there.

For context, as historian Scott Mingus, Sr. emphasizes, the original Soldiers’ National Cemetery was for those Union soldiers killed at the Battle of Gettysburg. There were no Black troops in that fight as existing Black regiments were in the South during the Battle of Gettysburg. The U.S. Colored Troops were organized later in the summer of 1863.

Historian D. Scott Hartwig points out: “we now know that there are five burials of African American soldiers in the Civil War section of the Soldiers’ Cemetery [in Gettysburg], but four of those soldiers were Spanish American War veterans who were buried here because it was the closest National Cemetery.” Only one Black Civil War veteran – Henry Gooden of the 126th United States Colored Troops, who died after the Civil War in Carlisle in 1876 and was not interred at Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery until 1884 – is buried there today.

A founder and prominent member of the Sons of Good Will, formed to acquire land for Black cemeteries, Basil Biggs, along with local Black Civil War veterans, is buried in the cemetery that the Sons of Good Will established in 1866. Since 1906, the year Biggs died and was buried there, it has been known as Lincoln Cemetery.

It’s on the outskirts of town in Gettysburg’s third ward, where most Gettysburg African Americans in that era lived.

How “Ticket to the Past” ends

Your “Ticket to the Past” visit winds to its finale with a view of President Abraham Lincoln’s train steaming into Gettysburg from Hanover on November 18, 1863. The next day – in Lincoln’s “few appropriate remarks” dedicating the Soldiers’ National Cemetery that Biggs helped create – the nation’s 16th commander-in-chief proclaimed a “new birth of freedom.”

The narrator then ends your visit with an open-ended challenge to honor the fallen, the freedom-seekers, the healers and re-builders of that era in our lives today.

“Ticket to the Past” is a bold, family-friendly, state-of-the-art, immersive, patriotic, and call-to-service visitor experience that you don’t want to miss.

Warning! Don’t aim your virtual reality headset downward; your legs and feet will not be there! But if you take the tour, you are sure to be grounded in good history and a moving experience.

Basil Biggs and a one-of-a-kind Hanover photograph

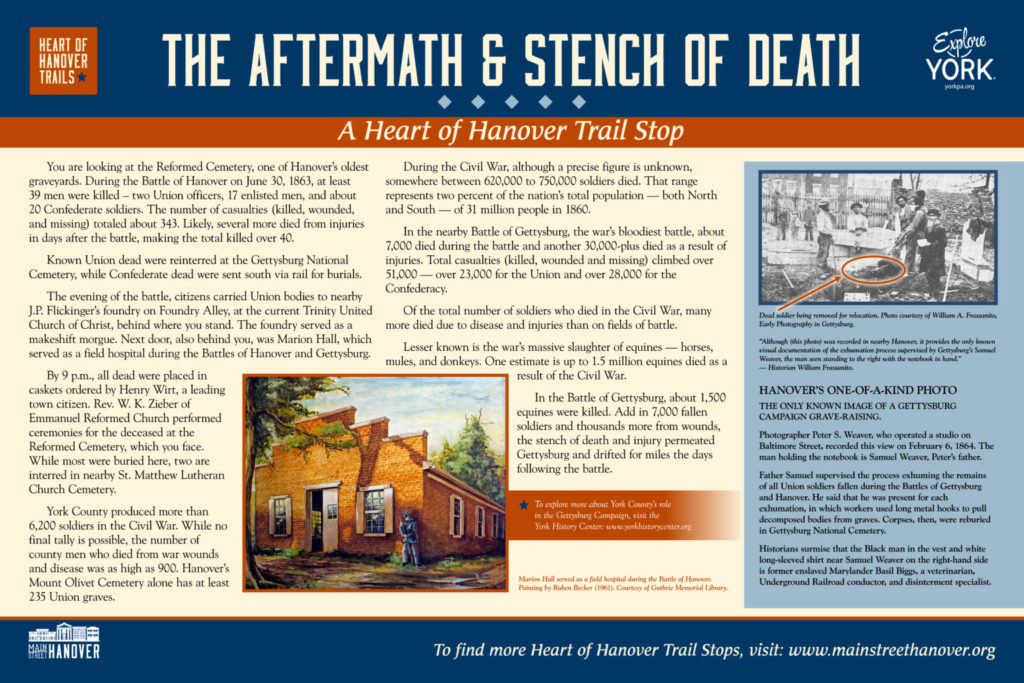

Part of Main Street Hanover’s Heart of Hanover Trails, a storyboard with a famous photo of a worker surmised to be Basil Biggs (in vest) and fellow members of the detail fronts the old graveyard behind Trinity United Church of Christ, 116 York Street.

From October 27, 1863, to March 18, 1864, according to supervisor Samuel Weaver’s official report, their morbid, stench-filled job was exhuming more than 3,000 bodies of Union soldiers killed in the Gettysburg Campaign for relocation at the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg. Only Union soldiers were intended to be buried there.

In “Early Photography at Gettysburg” (1995), historian William Frassanito points out the uniqueness of this photograph: “Although (this photo) was recorded in nearby Hanover, it provides the only known visual documentation of the exhumation process supervised by Gettysburg’s Samuel Weaver, the man seen standing to the right with the notebook in hand.”

Upon further investigation, according to Hanover historian John Krepps, this the only known photo of an exhumation in the Gettysburg Campaign and may be the first photo of an exhumation in the entire Civil War.

The Biggs family’s York connection

Basil’s son Calvin Biggs (died in 1910) was the father of another Basil (1881-1971), nicknamed Baz. Grandson Basil was a prominent York citizen and 60-year member of Faith Presbyterian Church, 50 North Duke Street, which was demolished in 1967.

A long-time employee of the D.S Peterman shoe company, grandson Basil also was a long-time trainer for the track and basketball teams of the York College Institute, York Junior College, and Gettysburg College. He was a trainer at York College Institute and York Junior College for 42 years.

Grandson Basil also was a founder and first scoutmaster of Troop 11 of the Boy Scouts of America and a charter member of Odd Fellows Lodge number 3118 (the Hand-in-Hand Lodge) of the Grand United Order of Oddfellows (the national Black Oddfellows organization).

With his Scout troop at an award ceremony at the White House, grandson Biggs also met President Warren G. Harding. According to historian Samantha Dorm, Basil, the grandson, is buried in Lebanon Cemetery in North York.

The questions

Despite the large numbers of African American Union soldiers, there is only Black veteran, Henry Gooden, buried at Gettysburg’s Soldier’s National Cemetery. Echoes of past racism still reverberate through the Civil War graveyards. To tell more of an inclusive story, organizations such as the Gettysburg Foundation, via the Gettysburg Lincoln Railroad Station, host virtual reality experiences like the one discussed in this article. Initiatives like this directly address the exclusionary practices of our past.

Are there other gaps in our history? What other stories need to be shared?

Related links and sources: Heart of Hanover Trails walking tour brochure; Heart of Hanover panels; Top photo from George Prowell’s “Prelude to Gettysburg;” Middle photo, Library of Congress; Bottom photo: Heart of Hanover Trails.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: Rita Mae brown: A welcoming place - Witnessing York