When social justice meets food freedom: Eliza and Ezekiel Baptist host Harriet Tubman

Farming by day, Underground Railroad by night

Steinhour Road, Newberry Township

The situation

Working the land to achieve racial equality dates back hundreds of years. In his autobiography, Booker T. Washington advocated for Black agriculture. His words reached Yorkers when a 1908 article in The York Daily quoted Washington, arguing that “proper farming methods” would lead to more economic independence.

Urban agriculture scholar Monica M. White says influential African Americans such as George Washington Carver and W. E. B. Du Bois endorsed agriculture as a way to reach higher racial equality. Du Bois, for example, laid the groundwork for collective farming through shared resources.

Locally, some Black families formed autonomous agrarian communities long before Washington, Carver, and Du Bois. For instance, a free Black couple, Eliza and Ezekiel Baptist, operated a farm on Steinhour Road in Newberry Township before the Civil War.

The witnesses

When they weren’t planting or harvesting their crops, the Baptists fought for freedom in other ways. Under the cover of darkness, they assisted freedom seekers.

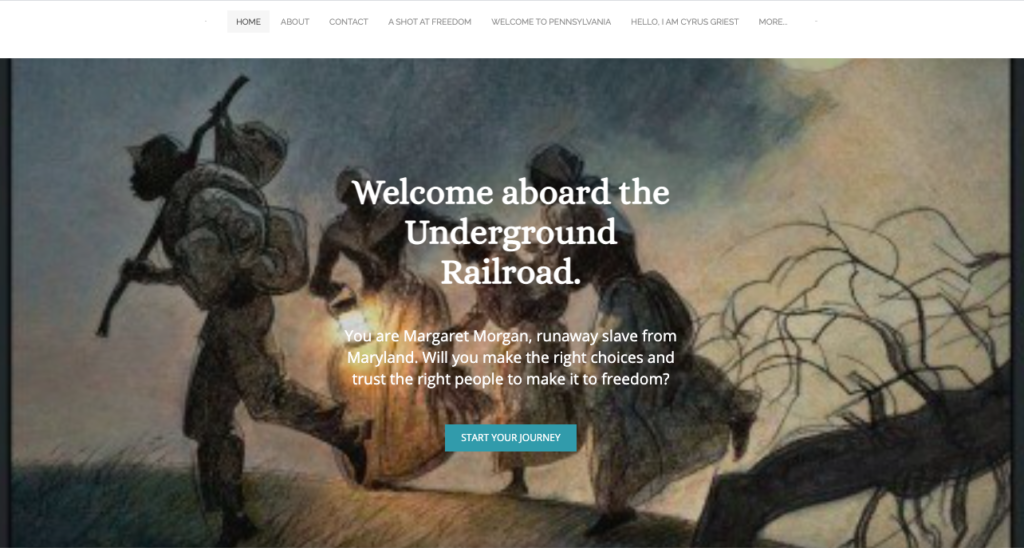

Known as the Underground Railroad, activists formed networks of aid to help people escape bondage. Abetting the enslaved was illegal, so the activism came with dangerous implications. Homes were used as safe houses, tucked away in rooms or secret hiding places until it was safe for them to move.

Sticking with the train terminology, the Baptists were known as “conductors.”

The couple had a lot to lose, but still they jeopardized their property and safety in the name of liberty. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 made it so even free states were responsible to return runaway slaves. Since they were understood to be property, assisting a person to freedom meant stealing.

That means that people escaping bondage weren’t safe until crossing into Canada. A lesser-known fact is that some Underground Railroad networks went south to Mexico and even the Caribbean.

If the Baptists would have gotten caught, they could have been fined or imprisoned. Even worse, the couple could have been attacked by vigilantes, resulting in a branding or lynching.

Their farm not only symbolized their freedom for the public to see, but represented a hidden sanctuary for those who needed to be kept a secret.

Alison Hope Alkon, author of Black, White, and Green: Farmers Markets, Race, and the Green Economy, looks at race and agriculture. She believes farmers, like York County’s Baptists, fused their Black and green identity into one influential performance. Finding themselves on the margins of a justice system that favored another race, this Black family used its farm as a tool for empowerment.

At the time, few knew of Ezekiel and Eliza’s humanitarianism. Their efforts were known by just a few trusted abolitionists. They worked alongside William Wright and Joel Wierman, Underground Railroad conductors from Adams County, and William C. Goodridge from York.

According to Scott Mingus’ research, the Baptists hosted Harriet Tubman, the most notable of all the Underground Railroad conductors, when she visited York County. Historians know little about her stay in the area.

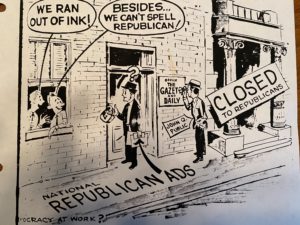

Later, locals learned of the couple’s efforts. A 1913 article in The Gazette described Ezekiel as “A colored man of strict, exemplary habits and was universally respected.” By 1875, the Baptists sold their farm, moving to the Mechanicsburg area. Three years later, Eliza died. Ezekiel stayed active in the agrarian community, investigating reports of horse theft before later passing in 1893.

The questions

Ezekiel’s and Eliza’s conviction against slavery was such that they were willing to risk their lives. However, it wasn’t for the accolades. Do we do what we do in the sheer hope for recognition? How can we exemplify the Baptists’ humble efforts of selfless humanitarianism?

Related links and sources: York Daily Record files; Scott Mingus’ article “Meet the Underground Railroad conductors who hosted Harriet Tubman in central Pa.” YDR Photos.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE

Pingback: urban-farming-thriving-agriculture-in-the-city

Pingback: Hometown History - Explore people, places and issues - Witnessing York

Pingback: Unsung York County Civil War sites to visit - Witnessing York