Saving lives through pioneering healthcare

Dr. Robert L. Ellis delivers York County’s first blood transfusions

1300 S George St, York

The situation

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, American casualties used 750 pints of blood. Only 750. This low amount isn’t from the lack of wounds – thousands of people died – but from a lack of sufficient supply of blood. This realization shocked Americans into giving blood.

Ever since this catastrophe, thousands of donors ensure wounded soldiers receive the necessary supply of blood they need to survive. In fact, Dr. Claud North Chrisman reported in the Evening Sun in July 1943 that two locals suffered from anemia due to over donating.

Donors could even sign their names to the bag labels, The Gazette and Daily reported in 1944. Service men and women were reminded that the very people they were fighting for, were also providing a lifeline.

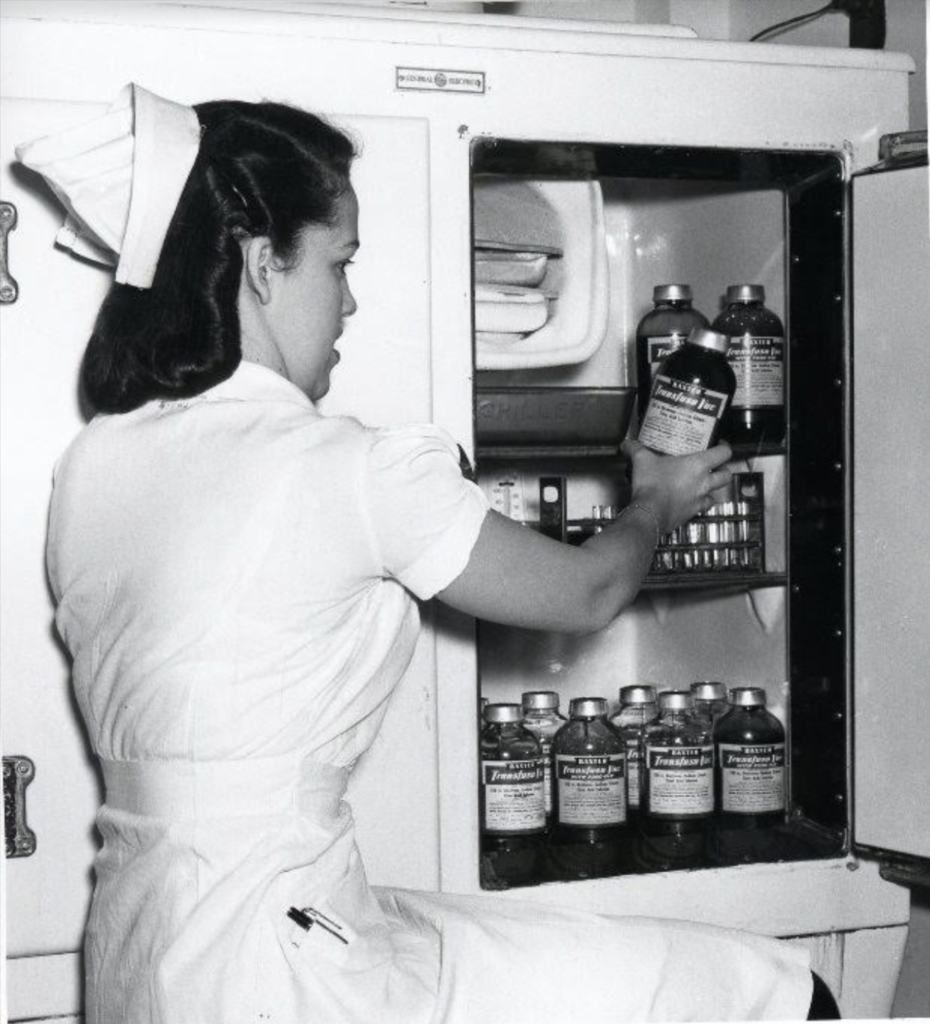

However, York County supplies are extreme lows in the spring of 2022. Only 24-48 hours worth of blood remain in the hospital refrigerators.

Jamie Kinsley dives deeper in her recent Wandering in York County blog article “York County donors asked to give in times of need: Blood demand doesn’t take a snow day.”

The witness

Blood transfusions are now standard practice, but in the 1920s this concept scared American surgeons. It wasn’t until 1923 that a medical doctor in York County attempted it for the first time.

That transfusion procedure represented a pivotal moment in county medical history.

Mary C. Lohss Burk of York City sustained severe blood loss. She was 28 years old, and about to welcome a baby into the world. However, her body was failing her. Without blood, she would perish right there on the delivery table.

Thankfully, Robert L. Ellis, a surgeon at York Hospital, was brave enough to try a procedure he had never tried before. Siphoning the blood from a donor, he pumped the invaluable bodily fluid into her veins.

It worked. Ellis saved her life, giving him the confidence to pioneer through more of science’s frontiers.

“Dr. Ellis successfully administered the first auto-blood transfusion in York in 1923,” a 1951 Gazette and Daily article reported.

After his first blood transfusion, he performed the first whole blood vein-to-vein transfusion followed by the first spinal anesthesia for abdominal and pelvic operations. When a spinal meningitis outbreak hit York, 80% of its victims died. However, after Ellis administered both intravenous and intraspinal injections, the death rate dropped to 50%. He would transfuse blood 25 more times before retiring from York Hospital in 1925.

One of Ellis’ most interesting procedures included auto-blood transfusions. He would siphon blood left in a patient’s abdomen from internal hemorrhage, injecting the blood mixed with anticoagulant into the patient’s veins.

While many American doctors scrutinized this strategy, Ellis’ bold actions saved the patient’s life until a blood donor could be located. Ellis would recognized by the Institute for Research and Biography of New York City for this pioneering work.

The questions

We celebrate Dr. Ellis’ courage to push the boundaries of medical science. That’s because it worked. He saved countless lives thanks to his knowledge and bravery. However, other scientists and doctors won’t earn a page on Witnessing York because their bold actions weren’t as successful. How do we, as pioneers in our own fields, know when to push the status quo? Who else serves as an example of heroism?

Related links and sources: Jamie Kinsley’s article “York County donors asked to give in times of need: Blood demand doesn’t take a snow day;” The Central Pennsylvania Blood Bank or The Red Cross; Photos from York County History Center.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE