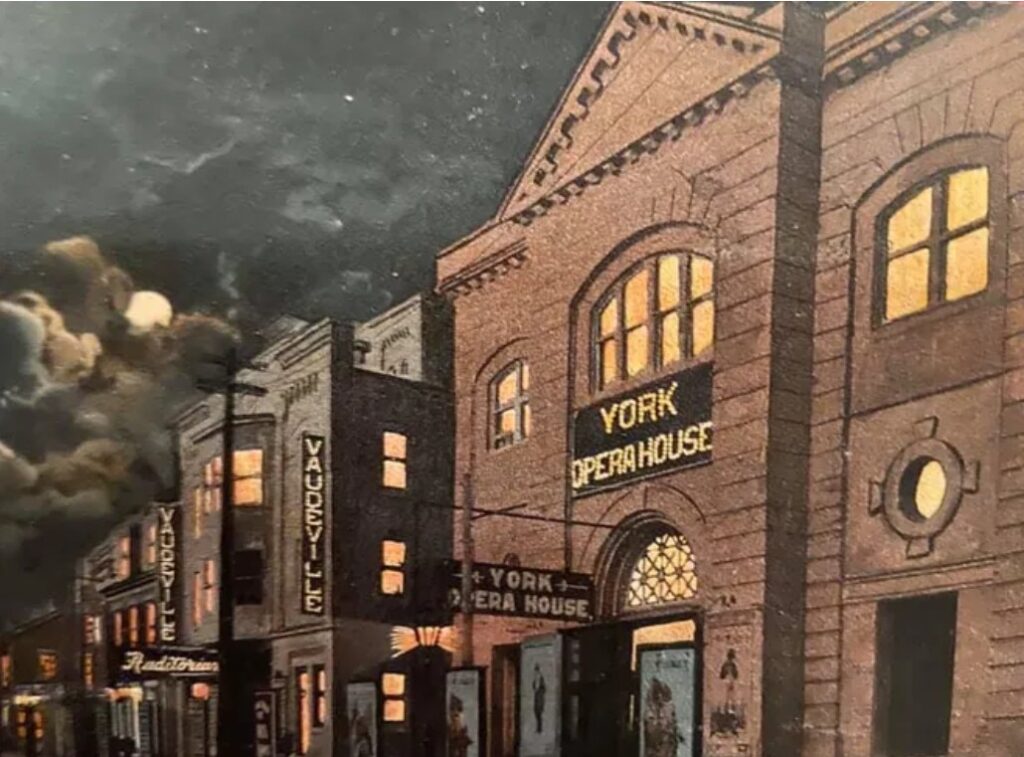

York Opera House, 1881 to 1936

York Opera House

31 S. Beaver St., York

The Situation

In 1881, John Sleeper Clarke, brother-in-law of Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth, starred in the 1881 opening act of the York Opera House. Clarke performed on the opera house’s news stage in productions “Toodles” and “The Widow Hunt,” popular in that day.

“The large and fashionable audience present was delighted with the performance,” a newspaper reported.

The opera house, designed by the York-based Dempwolf architectural firm, was not the first entertainment venue in York. Washington Hall, at King and George streets, then an International Order of Oddfellows (IOOF) Lodge, was one such predecessor.

But the York Opera House was built on South Beaver Street for big productions, and it would later be joined next door by The Orpheum, a vaudeville hall.

But even before its opening, friends and opponents sparred over the appropriateness of entertainment the opera house would bring to the community. Opponents also fought the decision to hold a York High School commencement in the new theater.

As the years passed, opposition cooled. The annual meeting of county teachers and evangelistic meetings of Dwight Moody and Ira Sankey used the facility. Harry Houdini, Douglas Fairbanks and other entertainers performed on its stage.

The York Opera House and its successors brought needed entertainment in York and York County during good times and bad.

The venue was succeeded in glitter and prestige by the Strand Theatre in 1925 and the neighboring Capitol Theatre in 1926.

That Strand opening in 1925 brought Michael J. O’Toole, a leader in the motion picture industry, to York. In remarks from the Strand’s stage, he clearly was aware that theaters, as venues in the arts, could evoke mixed feelings from a community.

For example, in the century after the York Opera House opened, York’s theaters would host sometimes controversial burlesque shows and later X-rated movies, particularly as older theaters declined. Some theaters also put into place Jim Crow practices, demanding that Black people sit in the balcony versus the lower level.

And a decade before his visit, the motion picture industry supported the screening of a racist movie, “The Birth of a Nation,” that was controversial and divisive in York County and nationally. And before that showing at the York Opera House, York hosted a Confederate general in what some people today say was the second surrender of York.

O’Toole must have entertained such moments before expressing high hopes to the capacity audience assembled at the Strand about what movies could do. He viewed motion pictures as a means to heal current racial and religious riffs across America. Movies could communicate about the lives and times of different people and add greater understanding that would contribute to the “Brotherhood of Man.”

O’Toole warned against censorship then in place or threatening the motion picture industry. He saw censorship as a First Amendment threat, the same as excessive government intervention represented for newspapers. No movie theater could stay in business if it offered a movie lineup that was offensive to audiences, and he called on theater owners and communities to work together to make movie houses institutions that are responsive to their communities.

The Witness

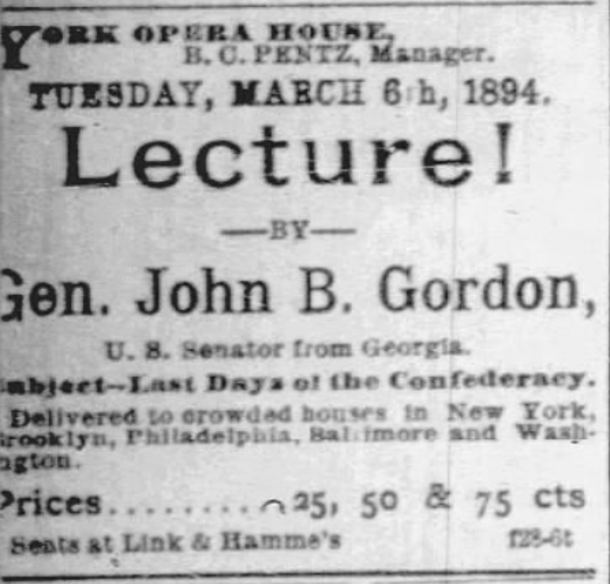

It’s worth a taking moment to revisit York’s reaction to the racially charged “Birth of a Nation” at the York Opera House. But we’ll start with another large gathering at the opera house, an event that also carried racial themes, Confederate John Gordon’s second visit to York. And we’ll end with a moment of redemption: when York’s premiere venue hosted Four Minute Men to keep audiences current in the dark days of World War I in 1918:

It was a late-winter evening in 1894, and the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment’s band accompanied a stately gentleman with a battle-scarred face and a soldier’s bearing along South Beaver Street to the York Opera House.

The theater wore the crown as the leading venue in town, and decorators were up for the grand occasion. An American flag was draped over the stage ready for the orator. Potted plants added a flourish to the set.

It was a scene befitting a Union Army general from the Civil War, which ended 29 years before, or a Medal of Honor recipient from York County or beyond.

The York Gazette revealed this orator: “The great personage was John B. Gordon, of Georgia.”

That’s the same Gen. John Brown Gordon who led the Confederate raid of York County in late June 1863, before the Battle of Gettysburg.

He was the rebel general officer who accepted York’s surrender after town fathers approached him in a remote farmhouse 10 miles west of York. It was considered by some today as a humiliating, game-changing moment for a proud community. His men marched into York the next day, June 28, and took down the American flag in York’s square.

Gordon and his men marched east to Wrightsville. In that Susquehanna River town, his 1,800 men overwhelmed a ragtag group of Union defenders and lobbed cannon shot on the town filled with civilians. One of the cannonballs killed a Black Union defender in the trenches.

Then his men lost a foot race to tug the Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge from Union control, but Yankee forces ordered the torching of the milelong span, stopping the Confederate advance.

In the meantime, Gordon’s men stole horses crucial for harvest, damaged crops, purloined unhidden supplies, burned bridges and pulled down telegraph wires. They terrorized York County’s people.

York lost its honor in seeking out Gordon to give him the keys to the surrendered city in a war in which at least 600 county men died on the battlefield and in camp fighting Gordon’s men and hundreds of thousands of others in gray. Perhaps it was the political kinship Democratic York County shared with Gordon. Maybe it was the spirit of reconciliation between the North and the South in that day. But in that spirit, consideration for a major player in the Civil War was lost: the formerly enslaved population of the South.

When Gordon mounted the opera house’s stage to deliver his “Last Days of the Confederacy” speech, he was given a pulpit to preach a sermon on the Lost Cause.

Such thinking, still around today, glorified an idealized society of honor and chivalry in the prewar South, contending that enslaved people were not mistreated. Lost Cause thinking shifted the authentic impetus for the war away from slavery to states’ rights and other spurious causes.

The newspapers carried no criticism of that moment.

But 22 years later, they did catch the spirit of discontent, and the York Opera House was the venue once again. It hosted the screening of “The Birth of a Nation,” a virulently racist film making the rounds across America. A newspaper carried a story about the Black community’s protest of its showing.

York did not have to screen the notorious film, set during Reconstruction and boosting the Ku Klux Klan, a group that Gordon was associated with before he appeared on the Grand Opera House’s stage. The mayor of Lancaster refused the showing of “The Birth of a Nation,” saying it libeled longtime resident Thaddeus Stevens. But western Lancaster County’s Columbia Opera House showed it. York’s Mayor E.S. Hugentugler allowed it, claiming he did not have jurisdiction to ban it.

The first visit brought 8,500 patrons to the opera house – an average of 1,700 viewers per show – and the film made a return visit several weeks later.

Perhaps Michael J. O’Toole, at the Strand’s opening nine years later, was hopeful that there wouldn’t be a repeat of this divisive film when he asserted motion pictures could promote racial healing.

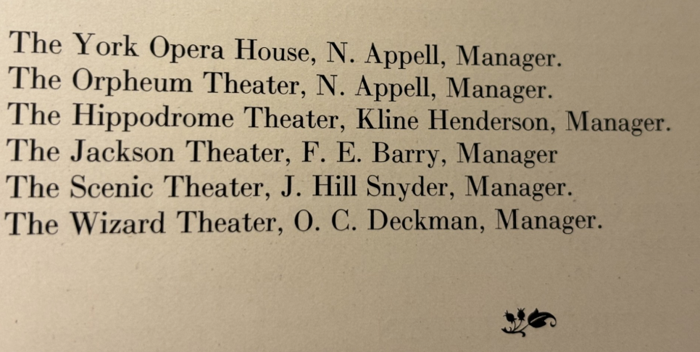

The York Opera House represented the best of what O’Toole could hope for in 1918. It was one of six York theaters as well as other entertainment venues to host Four Minute Men and the Speakers Bureau of the York County Committee of Public Safety, who would update audiences before shows about events in World War I. And raise funds for the war effort against great enemies in Europe.

+++

The York Opera House passed from the hands of the family of Nathan and Louis J. Appell in 1930 after 14 years of solo ownership. Warner Bros., the new owner, would have no use for the old house.

The York Opera House, designed by the noted York-based Dempwolf firm, was demolished in 1936, starting with its roof. When that work reached the dressing rooms, scores of photographs of those who had performed on its stage came to light.

As the demolition continued, scenery for turn-of-the-century productions were found. York residents in this Great Depression era collected scrap wood for their fireplaces. Around towns, yards were filled with wood from the once grand opera house. Finally, the lot was cleared from Beaver Street to Cherry Lane.

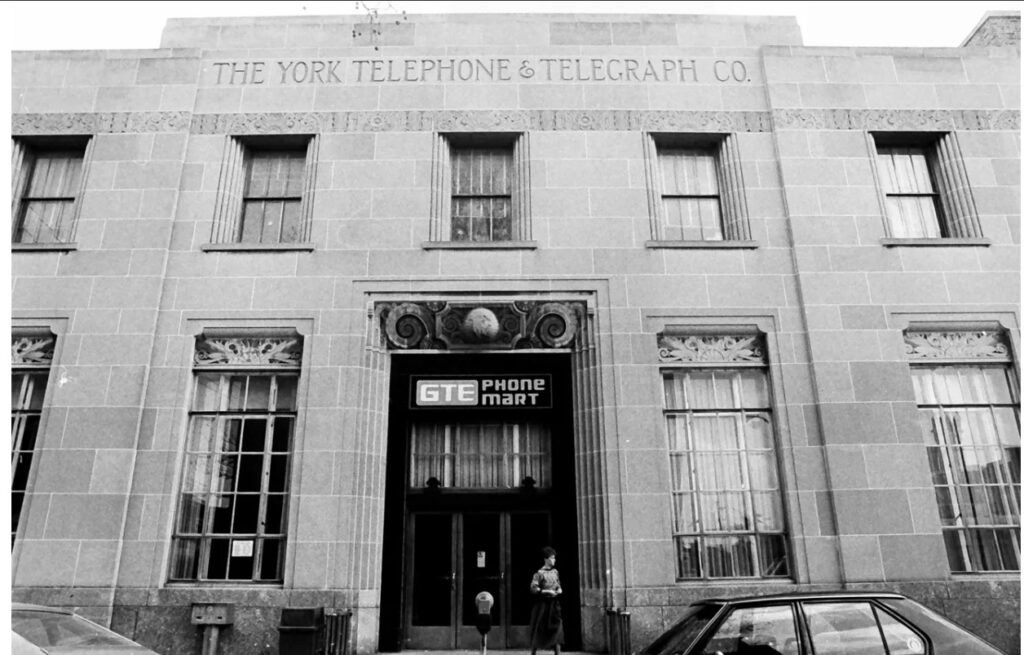

The site would later host a significant structure architecturally rendered by the second generation of the Dempwolf firm – the telephone company building with its ornate entrance.

The Questions

How do O’Toole’s ideas about the power of movies to bring people together connect to your own experiences with films or media? Have you seen a movie that helped you better understand people different from yourself?

Related links: Strand turns 100: This historic moment belongs to York PA community. Like we see with today’s Oscars, movies sparked racial division, immorality concerns a century ago | Joe McClure – pennlive.com. Photos: York Daily Record; Viewer, top photo, York Daily Record; Bottom photo, York Daily Record. Four Minutes Men image, “York County and the World War,” by Clifford Hall and John Lehn.

— By JAMIE NOERPEL and JIM McCLURE